[ad_1]

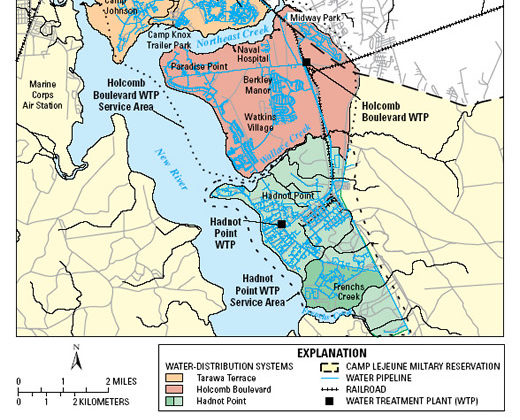

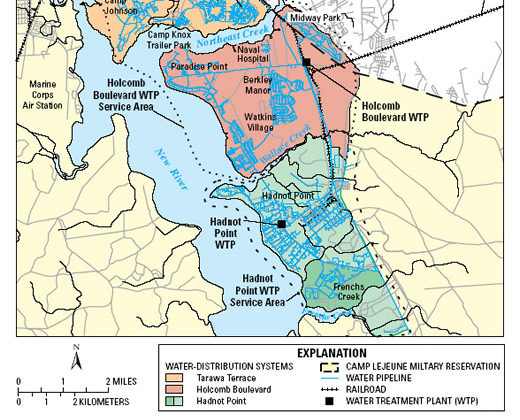

Image courtesy of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR)

By Lori Freshwater

The story of the chemicals at Camp Lejeune began almost as soon as the base did. World War II changed, everything. In May of 1941, construction began on a tent city using a commandeered family’s summer cottage as headquarters. This kind of transformation was going on across America. By the end of 1943, there were 345 main bases around the country. Most in rural areas. In Nebraska, 12 new Army air bases. In Texas, Andre Higgins went from a small boatyard operator in the Louisiana Bayou to building the amphibious boats some think won the war. Communities were transformed, and so was the country.

By February 1942, 19 platoon-sized barracks were constructed to provide billeting for about 1,400 men, raising the base’s capacity to 42,000. Some farmers were still trying to leave as the Marines were moving in.

The Hadnot Point fuel farm was built and consisted of 15 underground fuel tanks. Documents reveal the amount of diesel fuel spilled from those tanks — and that’s not even accounting for fuel lost during transfers or unreported leaks. A spill larger than 100,000 gallons is categorized as a major oil spill by the Coast Guard. The Hadnot fuel farm poured an estimated 800,000 gallons of fuel into the soil and groundwater. Records show that a water well on Lejeune in 1984 was contaminated by leaking fuel and yet it was left functioning for at least five months after samples showed the presence of carcinogenic chemicals.When fuel leaks underground – into the soil and groundwater goes petrochemicals.

In post-WWII the business of war in America was only getting started. A decade after farms became a tent city known as Camp Lejeune, Jacksonville North Carolina had already begun to feed off the Marine Corps base economically. Stores and dry cleaners and other businesses had already opened along the main road that runs along the edge of the base before it forks off into the main entrance. Enlisted Marines who were recruited east of the Mississippi were sent to the School of Infantry through that entrance to Camp Lejeune. Most of the young ones, some still teenagers, did not have cars so they walked wherever they had to go. One place they had to go was the dry cleaners.

A Greek family named Melts opened a family dry-cleaning business called ABC One Hour Cleaners and word got around they had the lowest prices to square away the young Marine uniforms. The dry cleaners were close so the Marines could get their uniforms cleaned and made straight and stiff with starch when they needed. And it was needed quite a bit. In 2003 there was a revision of the regulations, “the use of starch, sizing and any process that involves dry-cleaning or a steam press will adversely affect the treatments and durability of the uniform and is not authorized,” but in the decades before starch was the thing. Even for the Combat Utility Uniform, sometimes called Utilities or Camos.

But ABC Cleaners made more than money. It made waste: tons of waste from the solvent used to dry-clean the uniforms. Two to three 55-gallon drums of the solvent a month. About three gallons a day of toxic muck. And the thing that made the Melts’ business different than the other dry cleaners was that the owner used the muck to fill potholes in his parking lot and poured the rest into the drains. This muck got into the water supply and formed contaminated plumes that are still under the ground today.

In order to understand the extent of the damage done at Camp Lejeune, it is necessary to understand the chemicals. There were many more than will be discussed, but knowing about just four of them is enough to understand the magnitude of what happened at Camp Lejeune and what is still happening to human beings like me who were there.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) has been conducting studies on the water we drank at Camp Lejeune. Some of the chemicals we were exposed to are identified with long and complicated words, but are reduced to the benign evil of an acronym.

The ATSDR issued a position on our water, saying, “past exposures from the 1950s through February 1985 to trichloroethylene (TCE), tetrachloroethylene (PCE), vinyl chloride, and other contaminants in the drinking water at the Camp Lejeune likely increased the risk of cancers.” For those of us who were poisoned, this science is about our lives, and our deaths. But in addition to those chemicals, we would eventually learn we had also been exposed to the deadly carcinogen benzene.

First, let’s talk about what it means to be a volatile organic compound (VOC) because most of what we deal with falls into that category.

A volatile organic compound, or VOC, is responsible for the identifiable smells of familiar things like paint thinner and other household chemicals. They are low in water solubility which prevents them from dissolving in water. They also have high vapor pressure which means at room temperature they can vaporize and float up in their gaseous state causing another dangerous human pathway. It is possible to be poisoned by VOC’s by drinking them in your water and breathing them in your air if they are present in groundwater under your dwelling. For a deeper dive into the chemistry we turn to EHow’s Robin Higgins for a breakdown.

The first of the four main chemicals I will discuss is trichloroethylene (TCE) which is pronounced trī-ˌklȯr-ō-ˈe-thə-ˌlēn (tri-cloor-oh-etha-lene). Besides TCE, trichloroethylene is known by the benign yet somewhat appropriate sounding nickname Tricky. It is a chlorinated solvent, which is helpful for remembering because these chemicals dis-solve things like oil and grease. And trichloroethylene or TCE is a known human carcinogen.

Concerning Camp Lejeune, TCE is the chemical associated most with degreasers and cleaners used on equipment on the base. From radio parts to tanks, the TCE flowed freely and was disposed of without care. According to ATSDR:

Trichloroethylene is a colorless, volatile liquid. Liquid trichloroethylene evaporates quickly into the air. It is nonflammable and has a sweet odor.

The two major uses of trichloroethylene are as a solvent to remove grease from metal parts and as a chemical that is used to make other chemicals, especially the refrigerant, HFC-134a. Trichloroethylene has also been used as an extraction solvent for greases, oils, fats, waxes, and tars; by the textile processing industry to scour cotton, wool, and other fabrics; in dry cleaning operations; and as a component of adhesives, lubricants, paints, varnishes, paint strippers, pesticides, and cold metal cleaners

As far as the health effects, TCE can be linked to cancers and other illnesses. The ATSDR also shared strong evidence that it can cause cancer of the liver and kidney, as well as cancers of the blood like malignant lymphoma, and there is “some evidence for trichloroethylene-induced testicular cancer and leukemia in rats and lymphomas and lung tumors in mice.” Importantly, TCE is at the forefront of studies linking a chemical to immune dysregulation and autoimmune conditions. According to ATSDR, “Exposure to trichloroethylene in the workplace may cause scleroderma (a systemic autoimmune disease) in some people.” There have also been studies linking trichloroethylene to “decreases in sex drive, sperm quality, and reproductive hormone levels.”

Next we have a chemical that is often confused with TCE. Tetrachloroethylene, or Te-trə-ˌklō-rō-ˈeth-ə-ˌlēn (tetra-cloor-oh-etha-lean) which is another nonflammable and colorless liquid. Because of “TCE” being in use, this chemical is known as PCE. Other names for tetrachloroethylene include perchloroethylene, PERC, and perchlor. Most people can smell tetrachloroethylene when it is present in the air at certain levels. PCE is used as a dry cleaning agent and metal degreasing solvent but is mostly known, including in the context of Camp Lejeune, as the dry cleaning chemical. According to ATSDR, PCE exposure “may harm the nervous system, liver, kidneys, and reproductive system, and may be harmful to unborn children. If you are exposed to tetrachloroethylene, you may also be at a higher risk of getting certain types of cancer.”

From the ATSDR fact page:

People who are exposed for longer time periods to lower levels of tetrachloroethylene in air may have changes in mood, memory, attention, reaction time, or vision. Studies in animals exposed to tetrachloroethylene have shown liver and kidney effects, and changes in brain chemistry, but we do not know what these findings mean for humans.

Tetrachloroethylene may have effects on pregnancy and unborn children. Studies in people are not clear on this subject, but studies in animals show problems with pregnancy (such as miscarriage, birth defects, and slowed growth of the baby) after oral and inhalation exposure.

Exposure to tetrachloroethylene for a long time (years) may lead to a higher risk of getting cancer, but the type of cancer that may occur is not well-understood. Studies in humans suggest that exposure to tetrachloroethylene may lead to a higher risk of getting bladder cancer, multiple myeloma, or non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In animals, tetrachloroethylene has been shown to cause cancers of the liver, kidney, and blood system.

Two important things before closing on TCE and PCE – they degrade into other chemicals, including each other, and they are both linked to Parkinson’s Disease as well as the other illnesses mentioned above.

In the same way TCE and PCE might be thought of as twin names, the next two chemicals, also volatile organic compounds, benzene and vinyl chloride will be the next set. Both of these are petro-chemicals associated with petroleum products, most notably fuel.

The lesser known is vinyl chloride, otherwise known as (VCM) or chloroethene. This one can break down taking the form of the chlorinated solvents (TCE and PCE) we covered above. It is easy to see why it is called a chemical stew and why the only real solution is to keep them out of the water supply.

Vinyl chloride is another colorless compound, however this one is highly flammable and has a sweet odor. Vinyl chloride is among the top twenty largest petrochemicals being produced in the world, with America being the largest manufacturer. The thing most associated with vinyl chloride is polyvinyl chloride or PVC materials most commonly associated with the pipes in our homes and buildings.

According the the National Cancer Institute, “Vinyl chloride exposure is associated with an increased risk of a rare form of liver cancer (hepatic angiosarcoma), as well as brain and lung cancers, lymphoma, and leukemia,” all of which we see too much of in the Camp Lejeune community.

Perhaps appropriately, the last chemical we will discuss is the last one to be admitted to by the Department of the Navy: benzene. The people exposed to the water contamination at Camp Lejeune would eventually learn they had also been exposed to the deadly carcinogen benzene. Also clear and colorless, and highly flammable, but with a gasoline-like odor. When you put gas in your car, that smell is benzene. It is a petroleum byproduct and also is used in industrial solvents.

According to ATSDR:

Benzene was first discovered and isolated from coal tar in the 1800s. Today, benzene is made mostly from petroleum. Because of its wide use, benzene ranks in the top 20 in production volume for chemicals produced in the United States. Various industries use benzene to make other chemicals, such as styrene (for Styrofoam® and other plastics), cumene (for various resins), and cyclohexane (for nylon and synthetic fibers). Benzene is also used in the manufacturing of some types of rubbers, lubricants, dyes, detergents, drugs, and pesticides.

Benzene is a carcinogen - a well-established cause of cancer in humans. Benzene causes acute myeloid leukemia. Chronic exposure to benzene can reduce the production of both red and white blood cells from bone marrow in humans. And, “In animals, exposure to food or water contaminated with benzene can damage the blood and the immune system and can cause cancer.”

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has established a Maximum Contaminant Level Goal of 0 parts per billion (ppb) for benzene in public drinking water systems. In the early 1980’s one of the wells at Camp Lejeune measured 380 ppb.

The American Petroleum Institute concluded in 1948 that the only absolutely safe concentration for benzene is zero, and then the petrochemical industry launched a decade-long effort using science to create doubt. According to the Center for Public Integrity, “Experts say the petrochemical industry has bankrolled more research — at greater cost — than anyone but Big Tobacco, which coined the phrase ‘manufacturing doubt.’”

The government also appears to have attempted to shroud the truth about benzene. In 2010 the Associated Press found that a contractor “dramatically underreported” the level of benzene found in Lejeune’s tap water. The benzene was reported to be 38 ppb and then was omitted entirely when the Marine Corps was getting ready for a federal health review.

“The Marine Corps had been warned nearly a decade earlier about the dangerously high levels of benzene, which was traced to massive leaks from fuel tanks at the base on the North Carolina coast, according to recently disclosed studies,” the AP reported.

Kyla Bennett, a former EPA employee turned attorney, told CBS News that it was difficult to conclude there were some sort of innocent mistakes. “It is weird that it went from 380 to 38 and then it disappeared entirely,” she told CBS, “It does support the contention that they did do it deliberately.”

As with TCE and PCE, vinyl chloride and benzene the chemicals studies are linking with birth defects such as neural tube defects as well as male and female infertility, miscarriages, and both male and female breast cancer.

The chemical stew found at Lejeune is made of these volatile organic compounds. Sometimes called methyl ethyl death. They are volatile because they are not stable, able to vaporize, to enter soil and air as gas. To enter steam, with ultimate stealth. Which is exactly what they did for decades at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

[ad_2]