[ad_1]

Trials & Litigation

Unclean hands and executive-privilege scope debated after judge requires special master in Trump case

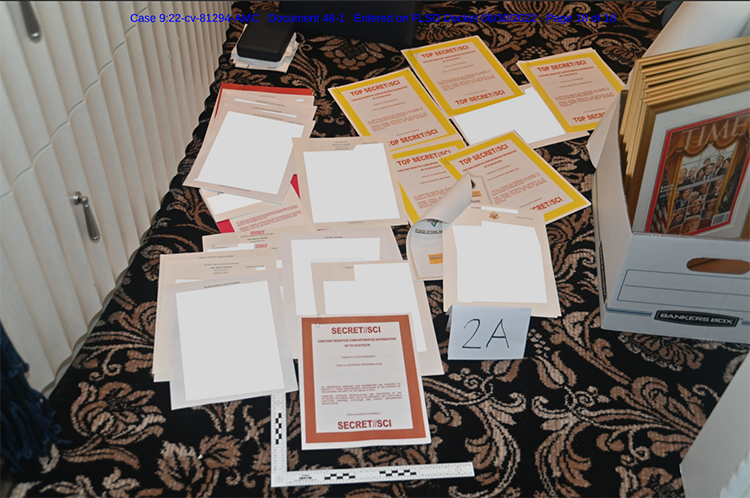

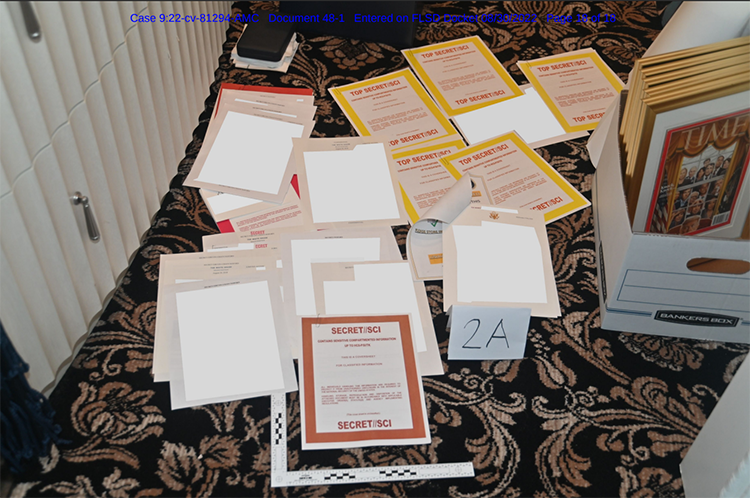

Photo from Department of Justice.

Legal experts are expressing surprise about two aspects of U.S. District Judge Aileen M. Cannon’s decision to appoint a special master to review documents seized from former President Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago home.

Experts are surprised that the special master will be allowed to review the documents for claims of executive privilege in addition to attorney-client privilege. And they are surprised the judge stopped federal prosecutors from using the materials in their criminal investigation during the review.

At least one expert also questions whether Cannon had the equitable-jurisdiction authority to act because of Trump’s “unclean hands” in retaining sensitive documents.

Publications with stories and op-eds include CNN (here and here), the New York Times and Slate. Experts tweeted their opinions here and here.The Volokh Conspiracy, meanwhile, considers the scope of “equitable jurisdiction,” one of the grounds that Cannon cited (along with “inherent supervisory authority”) for her authority to require the special master.

Cannon is a federal judge in the Southern District of Florida. Her Sept. 5 order authorizes appointment of a special master to review the seized property for personal items and material that could be subject to attorney-client and executive privilege.

Cannon also barred the government from reviewing and using the seized material from investigative purposes during the review. But Cannon allowed a classification review and intelligence assessment by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

Some of the experts who expressed surprise that Cannon enjoined the criminal investigation are:

• Orin Kerr, a law professor at the University of California at Berkely. Kerr tweeted that appointing a special master “is very odd” but “the bigger deal” is enjoining use of the seized materials for investigative purposes. “In the context of a contraband case, where proving the case is all about using the seized items, that injunction amounts to a judicial takeover of the executive branch’s investigation. I don’t see how a federal judge has the power to do that.” If there are government abuses, that has to be dealt with after the fact rather than through an injunction, Kerr tweeted.

• Paul Rosenzweig, a former homeland security official in the George W. Bush administration and prosecutor in the independent counsel investigation of Bill Clinton. He told the New York Times that Cannon’s decision appears to be “genuinely unprecedented” and enjoining the criminal investigation is “simply untenable.”

Some of the experts who expressed surprise about the executive-privilege review are:

• Peter M. Shane, who is a legal scholar in residence at New York University. He told the New York Times that executive privilege usually protects internal executive branch deliberations from disclosure. “Even if there is some hypothetical situation in which a former president could shield his or her communications from the current executive branch,” he said, “they would not be able to do so in the context of a criminal investigation—and certainly not after the material has been seized pursuant to a lawful search warrant.”

• Former Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. He tweeted that executive privilege “isn’t some post-presidential privilege that allows presidents to keep documents after they leave office. At most, it simply means these are executive documents that must be returned to the archives. It doesn’t in any way, shape or form mean they can’t be used in a criminal prosecution about stolen docs.”

• Former White House ethics czar Norman Eisen and Democracy 21 founder Fred Wertheimer, who were authors on an amicus brief in the documents case. They wrote in a Slate op-ed that the Presidential Records Act and legal precedent show Trump “cannot successfully assert executive privilege against the executive branch as it conducts executive functions.” They cite Nixon v. Administrator of General Services, a 1977 U.S. Supreme Court case that upheld a federal law directing the GSA to seize former President Richard Nixon’s presidential materials and to preserve those with historical value. The court held the law didn’t violate the principle of separation of powers.

Writing at the Volokh Conspiracy, Notre Dame law professor Samuel Bray opines that Cannon didn’t have equitable jurisdiction in the case because of the unclean-hands principle and two other principles of equity jurisdiction.

First, Bray says, a longstanding principle of equity is that courts won’t intervene in criminal cases, and that includes criminal investigations by the U.S. Justice Department.

Second, courts can’t exercise equitable jurisdiction absent a proprietary interest for the plaintiff. Here, Trump has no property right in the classified documents seized, even though he does have a right in his personal items.

Third, “equity offers no relief to those who come into equity with unclean hands,” Bray says.

“If former President Trump commingled his personal effects with classified documents belonging to the United States, then that is not a reason to allow him to restrict use of the government’s property,” Bray writes. “Instead, that is a reason to deny him any relief to protect his own property.”

[ad_2]