[ad_1]

Located between the Arno and Serchio rivers in Tuscany, central Italy, is a white marble bell tower. Construction began in 1173, and plans called for the bell tower to reach eight stories in height. After the construction of the first three stories, I imagine the chief engineer stood back, took a hard look at the growing tower and thought to himself, “Hmm, sono solo io, o questo cucciolo sta iniziando a magra?” (Translation: “Hmm, is it just me, or is this puppy starting to lean?”)

Then, I suspect, a construction laborer walked up next to the chief engineer, hesitated for a few seconds and said, “Beh, odio dire che te l’avevo detto, ma…”. (Translation: “Well, I hate to say I told you so, but…”)

Officially completed almost 200 years later in 1370, the Leaning Tower of Pisa continued to slowly tip over. In fact, by 1990, it was leaning 5.5 degrees (or approximately 15 feet) from the perpendicular — the most extreme angle yet. That year, the monument was closed and the bells removed so engineers could begin extensive work to stabilize the tower.

What that chief engineer learned when he first observed the leaning of the tower was a construction term called “difetti compositive,” or, in the English translation, “compounding defects.” In other words, if the dirt under the foundation is not perfect, the rest of the structure as you move upward will increasingly fail. The dirt is, in essence, the first building block.

The dirt under the foundation of the Leaning Tower of Pisa was abysmal, and that’s being kind. The dirt that was meant to support the entire weight of the structure was composed of clay, sand and seashells. No wonder it began its slow descent toward falling over.

So, what does the dirt under the Leaning Tower of Pisa have to do with an agency’s use-of-force training program? That’s a great question, and the answer is plenty! If the “dirt” under the foundation of your use-of-force training program isn’t right, compounding defects are sure to arise. How do you know if this important building block under the foundation of your use-of-force training program has been properly prepared? We can find out by asking this question: “Is your program based on the two most important outcomes for training use of force?”

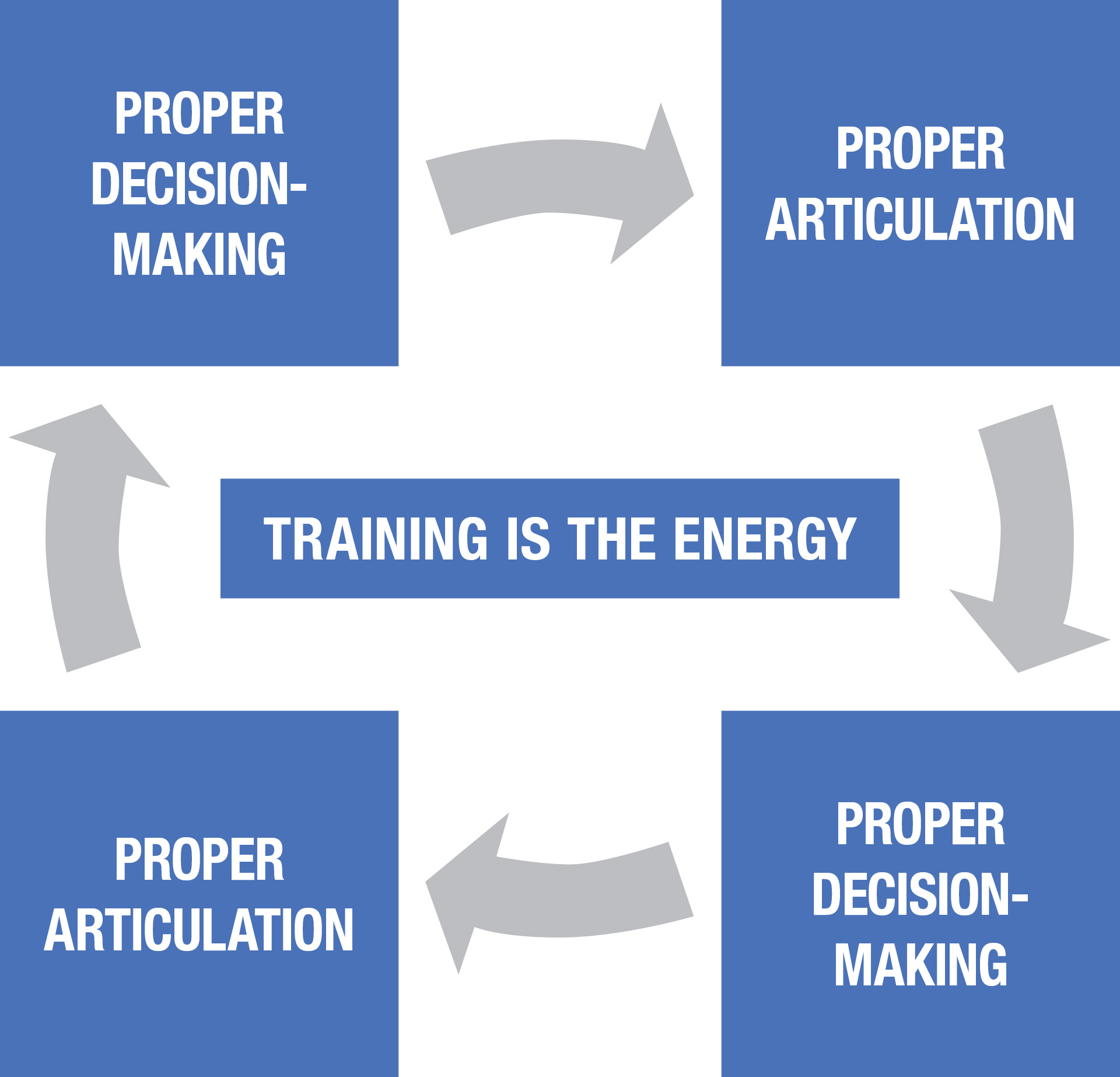

The two most important outcomes for use-of-force training are proper decision-making and proper articulation. They should be the dirt under the foundation on which your use-of-force training program is built.

Why are these two outcomes most important? First, if an officer makes an unreasonable force decision, it’s pretty much over for them from that point. No amount of articulation is going to turn an unreasonable force event into a reasonable one.

Second, an officer must be competent in properly articulating their force event after the fact, both in written reports and verbal articulation.

A third reason why these two outcomes are most important involves the duty of an officer to intervene in an unreasonable force event. The better trained an officer is at properly evaluating the reasonableness of force events, the quicker that officer can recognize the problem and intervene if necessary.

Ultimately, the better an officer becomes at articulating in support of a force event, the better they become at making proper force decisions. But it takes training on a consistent basis to develop officers into knowledgeable and skilled use-of-force evaluators. Additionally, use-of-force training should be developed and delivered foundationally.

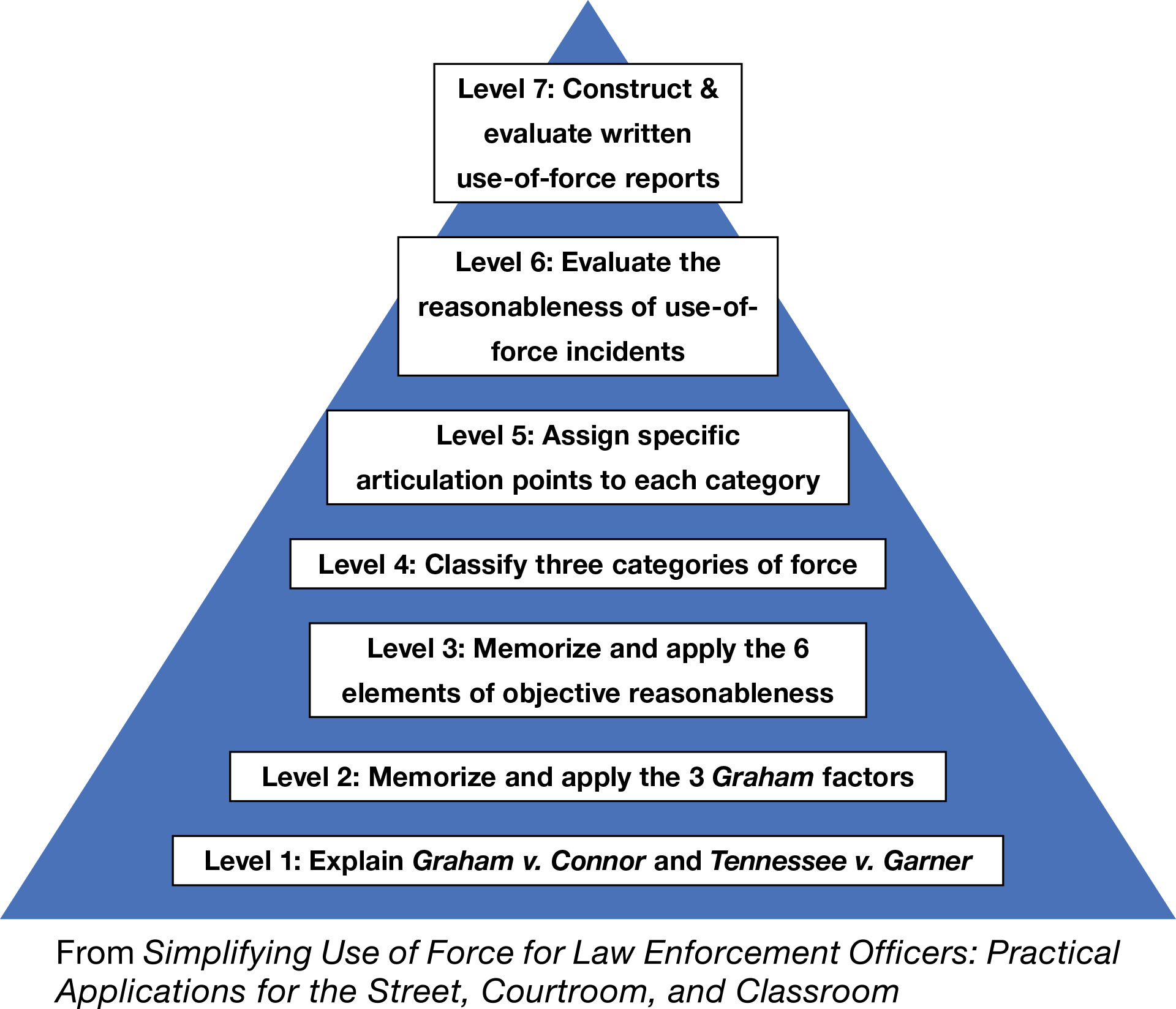

Years ago, I developed a use-of-force training model that has turned officers into successful use-of-force evaluators. I based these levels on Bloom’s taxonomy of learning. Bloom’s taxonomy is a hierarchical model that places learning objectives into varying levels of complexity, from basic knowledge and comprehension to advanced evaluation and creation.

Here is that use-of-force model:

- Level 1: Explain Graham v. Connor and Tennessee v. Garner.

- Level 2: Memorize and apply the three Graham factors.

- Level 3: Memorize and apply the six elements of objective reasonableness.

- Level 4: Classify three categories of force:

- Hands-on/less-lethal

- Deadly force

- Deadly force on a fleeing felon

- Level 5: Assign specific articulation points to each of the following three categories:

- In a hands-on/less-lethal incident: Articulate the applicable Graham factors at the moment the hands-on/less-lethal force was intentionally applied.

- In a deadly force incident: Articulate means, opportunity and jeopardy together in time and space at the moment force deadly force was intentionally applied.

- In deadly force on a fleeing felon: articulate a) if the officer had probable cause to believe the fleeing felon had used, attempted to use or threatened to use deadly force against another prior to fleeing, and b) did the officer believe the application of deadly force was immediately necessary to stop the deadly danger posed by the fleeing felon?

- Level 6: Evaluate the reasonableness of use-of-force incidents.

- Level 7: Construct and evaluate written use-of-force reports.

Once officers become proficient use-of-force evaluators, agencies can begin instituting scenario-based training to further infuse the concepts through real-life applications.

One item I feel compelled to address is the issue of use-of-force report writing. In my travels around the nation, I’ve found very few agencies that include use-of-force report writing as part of their overall training program. Building an officer’s skills in composing and evaluating use-of-force reports is an incredibly important component in improving their ability to properly articulate in support of a force event. If the officer’s agency isn’t providing this type of training, it leads me to ask one sobering question: “When, then, does an officer write their first use-of-force report?”

While use-of-force or response-to-resistance training isn’t a perfect science, there are ways we can train that can dramatically build the decision-making and articulation skills of officers. The benefits of such training can be felt by officers, their agencies and the communities they serve. Ultimately, the benefit of properly preparing the dirt under the foundation of your use-of-force training program can be felt out on the street, where it counts the most.

Don McCrea is president of Premier Police Training and has 35 years of law enforcement experience. He specializes in non-escalation, de-escalation, search and seizure, and use of force. Don is a nationally and internationally certified instructor and has an IADLEST nationally certified course, “Confident Non-Escalation: This Is Where De-Escalation Training Begins.” He currently serves as academic program coordinator for a four-year law enforcement degree program at South Dakota State University and provides consulting and training services for law enforcement agencies, the U.S. DOJ, COPS Office and CRI-TAC. Don has also had a long and happy relationship with dirt, from playing in it with his Tonka trucks as a kid to training use-of-force concepts today. He can be contacted through PremierPoliceTraining.com or reached by email at don@premierpolicetraining.com.

As seen in the July 2022 issue of American Police Beat magazine.

Don’t miss out on another issue today! Click below:

[ad_2]