[ad_1]

Glenys Kinnock, the former MEP and minister of state at the Foreign Office, who has died aged 79, was a determined feminist who realised her political ambitions by securing recognition as an international stateswoman, after having spent nearly 30 years as a classroom teacher.

Despite her delight in her second career, Lady Kinnock of Holyhead, as she became in 2009, on taking office in the last year of the then Labour government, was the first to insist that she would greatly have preferred to fulfil her earlier ambition to help achieve the election of a Labour government under the leadership of her husband, Neil Kinnock.

A democratic socialist, she was raised by politically aware parents to regard herself as a citizen of the world. It meant that she was always her own person, knew her mind and never accepted attempts to label her as a woman or a political activist, still less as a wife. She deftly developed her own role as the equal partner in a mutually supportive marriage and became a model for modern leftwing and thoughtful feminism.

She cooked and read and ran what the Welsh might call “a proper tidy house”, yet was also curious and outward-looking, and everything she did was filtered through the prism of her political beliefs.

Clever, funny, smart and resourceful, she had the ability to communicate with anyone; it was particularly noticeable in her instinctive connection with small children. This was almost certainly the same skill that enabled her to handle other politicians so expertly. She was also mischievous: she and a girlfriend once pretended to be models in a shop window, standing stock still and then changing their pose to startle passers-by.

Glenys was the daughter of Cyril Parry, a railway signalman and merchant seaman during the second world war, and his wife, Elizabeth (Bet), who took in washing as a young woman and then ran a cafe. She had an elder brother, Colin, and was born in a railway cottage with no running water, gas or electricity, in Roade in Northamptonshire. Her first political campaign was run by Cyril, delivering Labour leaflets from her pram in the 1945 general election.

The family were Welsh-speaking chapel-goers and returned to their native Anglesey (Ynys Môn) when Glenys was two. She would learn about politics from her father in the signal box at the end of the line in Holyhead. He was a strong trade unionist and had become an internationalist from his service at sea. There was much family amusement that he was discovered to be colour blind only on retirement as a signalman.

After school in Holyhead, Glenys studied education and history at University College, Cardiff. She had joined the Labour party, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and the Anti-Apartheid Movement in her mid-teens and political activity was thus an early mission in Cardiff.

“Are you the man from the socialist society?” she asked a red-haired, second-year student in the canteen. Neil confirmed that he was the chairman and persuaded her shortly afterwards to become the secretary. They married five years later, in 1967, their wedding symbolised with a ring in white Welsh gold, in order not to buy gold from South Africa. Their son, Stephen, was born in 1970 and daughter, Rachel, in 1972.

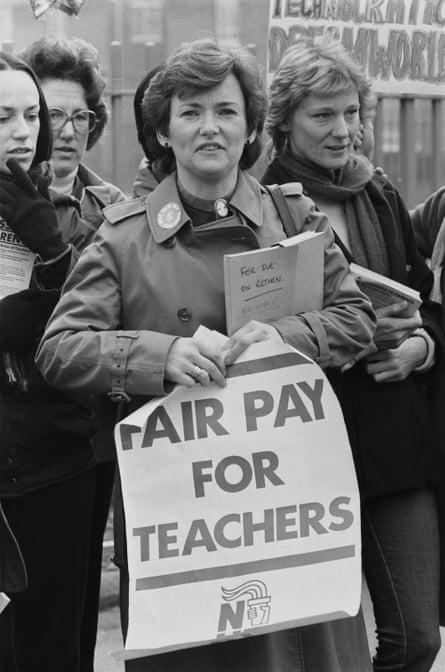

Glenys always wanted to teach, lining her dolls up before a toy blackboard as a girl, and took on posts in Splott, a suburb of Cardiff, and Abersychan, near Pontypool, before the family moved to Kingston in south-west London after Neil’s election to the Commons in 1970. She taught part time until her own children went to school and full time thereafter. The Kinnocks moved again, to Ealing, to avoid the 11-plus selection for their children. In the course of her career Glenys taught secondary, primary, infant and remedial classes and was a highly active member of the National Union of Teachers.

Press attention had focused on her as the stylish, articulate wife of a rising Labour party star, but she studiously avoided personal publicity until Neil was on the verge of becoming leader in the wake of Labour’s disastrous 1983 election result. She gave a confident early TV interview at one of several supportive visits to Greenham Common in the early 1980s, travelling there with a group of female friends to join the protest against siting Cruise missiles in Berkshire. On one occasion she walked the perimeter fence of the defence base, scrambling several miles through thorn bushes to do so.

Her role as the leader’s wife was not easy. The couple had to negotiate much troubled terrain with a largely rightwing press attempting to portray Glenys as the “eminence rouge” in the Kinnock kitchen or “Lady Macbeth” in the living room. They had been dubbed “the power and the glory” at university and there was much public debate about who was which. Her views were often more radical than those of her husband and she expressed them forcibly in private – about the extent of his political reforms and revisionism that he regarded as vital to secure Labour’s electability after its lurch to the left in the late 70s. But she was always loyal in public.

They also regarded it as vital to try to protect their teenage children from hurtful publicity. On one occasion a poster site within view of the family home showed a caricature of Neil hanging by a noose (to make a point about a hung parliament) which they sought to have removed. They were also highly sensitive about details of their family life being leaked, as happened frequently. In contrast, a Daily Mirror initiative to bring more than 100 members of the Kinnock and Parry families together to portray them as a cross-section snapshot of life in Britain before the 1987 election was joyfully embraced.

Glenys had a streak of ruthlessness that cost her friends, and she became ambitious on her own behalf. Neil resigned the Labour leadership having failed to win office in 1992 and Glenys decided – as her husband contemplated appointment as a European commissioner – that she would seek selection for the European parliament. At the time South Wales East was the safest seat in all the member states in Europe but Glenys fought it like a marginal. She was elected in 1994 by 145,000 people, with a majority of more than 120,000 on 74% of the vote. She was an MEP until 2009, for the latter two elections as a member for Wales.

She stood out as an MEP as someone who knew her stuff and had grown greatly in personal confidence during her husband’s political prominence. Glenys brought her political expertise and personal passions to the causes she espoused, primarily those of human rights, feminism and poverty in the developing world.

Travelling widely, particularly in Africa and the Caribbean, from 2001 until 2009 she co-chaired Europe’s joint parliamentary assembly with the ACP (Africa, Caribbean and Pacific) group. She was the Labour spokeswoman on international development in the European parliament and helped found a charity, One World Action, in 1989.

It was the completion of an extraordinary metamorphosis and with her husband as transport commissioner and then as vice-president of the commission between 1994 and 2004, they became Europe’s foremost power couple – passing each other on the escalators at London Heathrow.

She stood down from Europe after 15 years to join Gordon Brown’s government as minister of state, initially for Europe and subsequently for Africa. She accepted a life peerage, joining her husband, who was already a member of the House of Lords, and from 2010 until 2013 was opposition spokeswoman on international development.

She accepted numerous honorary posts associated with her interests, including membership of the board of the European Centre for Development Policy and of the council of the Overseas Development Institute. Her books included By Faith and Daring (1993), a collection of interviews with notable women.

Glenys was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s six years ago, and retired from the Lords in 2021.

She is survived by Neil, Stephen and Rachel, and five grandchildren.

[ad_2]