[ad_1]

I think it is safe to say that almost every single police department in our country has dealt with a “swatting” incident (or something similar) over the past 15 years. In fact, “swatting” — false alarm calls to entice a police response — have become so common that it is almost expected for somebody to become a target of this type of crime from their online presence, whether grievances aired via social media, online gaming feuds or a furtherance of the zeitgeist of “cyberbullying.” These types of crimes (and yes, they are, in fact, crimes) have become a cultural phenomenon, leaving police departments viewing them as more of a nuisance versus something that warrants further investigation. I personally can tell you of many police departments that opt not to investigate these crimes due to misconceptions of how these types of calls are facilitated, or unjustifiably believe that these cases are pointless since the suspect is likely outside their jurisdiction. It leads to a perfect storm of enabling those who opt to commit “swatting” calls, fostering a mindset that emboldens these actors to think they likely won’t be caught, and the emergence of a pattern of criminal behavior I have dubbed “serial swatting.”

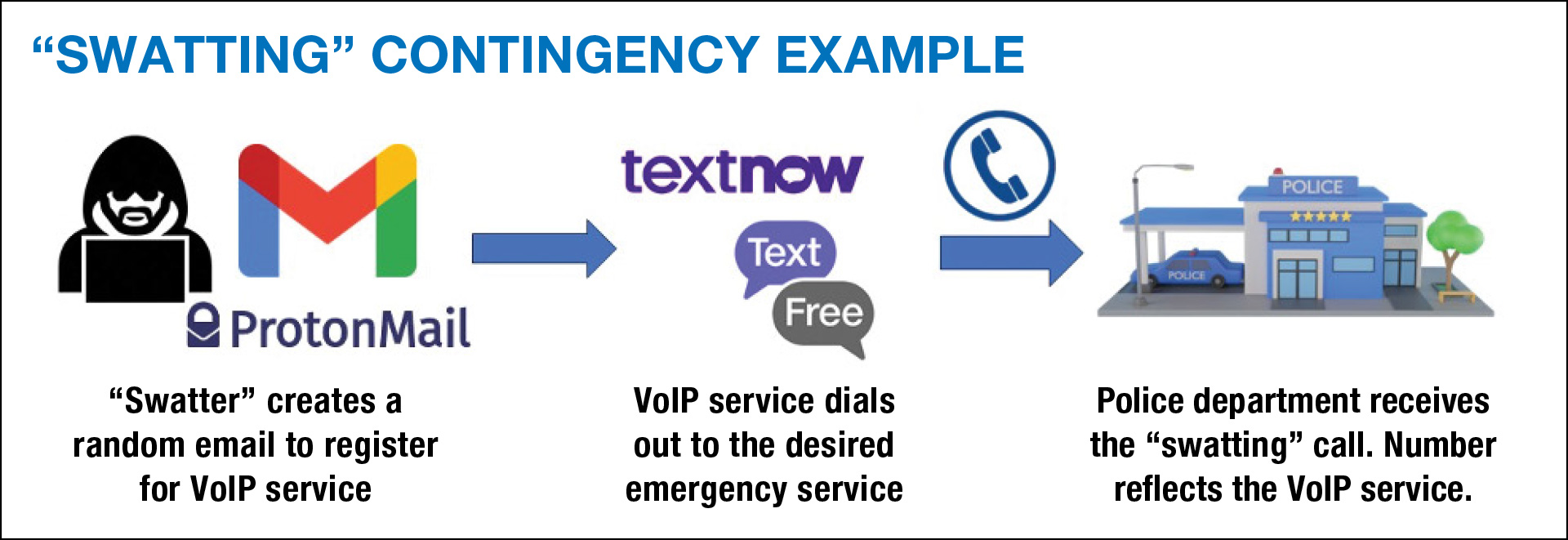

In my article “Investigating Scam Phone Calls,” published in June 2020 in the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin (see tinyurl.com/3sb65c57), I highlighted how the use of readily available voice over internet protocol (VoIP) services facilitate the myriad telephony-related crimes. Whether it is spoofed calls, scam calls, or evolving trends like “smishing” (SMS phishing) or “sextortion,” VoIP services like TextNow or TextFree are often the medium utilized. While the aforementioned services are probably the most commonly abused, there are many more services that are free for users and only require you to register with an email. Typically, if a bad actor were going to abuse VoIP services for nefarious means, they merely need to create an email to register an account.

Most VoIP services are attributed to a point of presence (POP) provider, such as Bandwidth LLC or Sinch–Inteliquent. POP providers are the way the VoIP numbers connect to the Public Service Telephone Network (PSTN) and dial numbers attributed to telecom providers. It is important to understand that POP providers often provide this interoperability service to many VoIP companies, so when a legal order is served to a POP company to compel a subscriber/attribution to a specific phone number, they will often respond with the company they provide the POP service for. Case in point, Sinch–Inteliquent can respond that a specific number, (101) 555-1234, is attributed to TextNow and subsequently issue legal notice to TextNow legal compliance to compel attribution. While this process is often lengthy and may seem unfruitful, it is merely the first step.

More often than not, a “swatter” will create an email and contemporaneously register for a VoIP service within a matter of minutes. Free email services like Gmail and ProtonMail allow users to create accounts quickly and easily, and because of this, “swatters” will often create a one-time-use mailbox specific for their intentions. It is important to identify this email and see if it is a service that will respond to legal notice. While Gmail accounts are relatively easy to create, Google maintains a lot of valuable data and information on the registrant. VoIP services merely maintain IP session records related to calls, which savvy “swatters” will obfuscate by virtual private network (VPN) service. Insomuch, Google, for example, collects a lot more data that can help attribute a singular user as opposed to standard free VoIP services. Something I feel would be a best practice is, once an email account has been identified, to issue a search warrant for a responsive email service as opposed to a subpoena. In the search warrant, ask for the entire mailbox as well as all data that can be compelled. Case in point, if we have identified a Gmail account attributed to a VoIP service, compelling Google to provide the entire mailbox, search history, logins, etc., associated with that Google account will provide an investigator with a treasure trove of information. Most email services will provide entire email mailboxes in the format of “.mbox,” which would require the investigator to have an MBOX viewer. One such free tool is available on a GitHub repository, but many forensic data and analytic programs provide MBOX viewing support.

While many in law enforcement view these types of investigations as “techy” or cumbersome, it is important to understand that a lackadaisical approach to these cases allows the “swatting” culture to become more robust. Don’t believe me? Well, there are “swatting” Discord channels where “swatters” encourage others to tune in to watch or listen to the “swatting” in real time. For example, you can see a YouTube video (tinyurl.com/42nrut4d) of gamers being “swatted” while live streaming (as of July 2023, the video has amassed over 35 million views). Other “swatters” have found a way to financially profit from “swatting,” such as the 2017 case of the Jewish center bomb threats suspect who turned out to be an Israeli teenager. Currently, there are services advertised on Telegram and the darknet that promote “swatting-for-hire” actors who will do your bidding for payment in various cryptocurrencies.

When you receive a response from a VoIP service, I think it’s imperative to look at all of the calls that the suspect facilitated. You will likely find other police departments’ phone numbers in the call history. I wholeheartedly believe contacting those police departments to try to get an audio copy of that call, or at least find out what the call entailed. “Swatters” will often use the same story in the call to illicit a police response, such as, “Came home to a spouse cheating and killed them and tied the children up and are holding them hostage.” It is important to understand that VoIP services cannot call 9-1-1 and can only call the publicly available numbers, usually the “nonemergency” lines, which makes it relatively straightforward in identifying other possible victims of the same “swatter.” Another evolving trend is for “swatters” to call the National Suicide and Crisis Lifeline instead of calling a police department directly, as a way to proxy “swat” the intended victim by saying the victim is suicidal or wants to commit “suicide by cop.” This is what makes the previously mentioned investigatory advice a bit more difficult since now you would need to obtain the call records from the National Suicide and Crisis Lifeline and possible recordings as a first step.

A term that I had previously mentioned in this article is “serial swatter,” something that has become more and more common as “swatting” is now mainstream and a twisted trend. While there are certainly no shortage of “swatting” incidents across the country, it is imperative to identify trends that can be conducive with “serial swatters.” For example, in December 2022, Kya Nelson and James McCarty were federally charged for a series of “swatting” incidents that incorporated the unauthorized access of a victim’s Ring camera. McCarty was also charged for a series of “swatting” incidents across the country to schools and police departments. The motivation behind it all? Great question! A reason could be that maybe police have become so complacent with viewing these types of cases as merely hijinks as opposed to crimes. Currently, there is a “serial swatter” who has been calling in threats to schools and other public facilities across the U.S. for over two years now, as highlighted in American Police Beat and NPR.

While “swatting” is a rather specific criminal genre, we also need to understand that VoIP abuse is not strictly compartmentalized to “swatting.” Many scams and other elements of criminality utilize the same tradecraft, and it’s a very profitable criminal enterprise. Earlier this year, the mastermind behind the call-spoofing service “iSpoof Club” was sentenced to 13 years in prison in the United Kingdom. While there are much more sophisticated methods that actors can employ to commit telephony crimes, ranging from international virtual SIMs ported to “SIP phone” apps like Linphone, most “swatters” will often be using services like TextNow or TextFree based on the low learning curve and minimal skill set required to be successful.

As police departments find themselves fielding more and more “swatting” calls, the question I ask is, what has been done to attempt to investigate these cases? I feel a call to action is very much overdue. Until law enforcement as a whole views “swatting” as the societal scourge and blight it truly is, only then can we expect any progress to end the growing trend.

[ad_2]