[ad_1]

Share and speak up for justice, law & order…

“Never bring a knife to a gunfight,” may now be an outdated axiom in light of some new human factors research I have been conducting with nationally renowned knife throwing expert, Matthew Dunn of Throwstar® Tactical in Swedesboro, New Jersey.

For over forty years, I have been a law enforcement, military, and civilian use of force instructor, educating thousands of professionals and civilians in various less-lethal and lethal force options and weaponry. With a background in law enforcement, medicine, forensics and applied science, I have applied those skillsets in conducting research into how psychophysiology, human factors and applied science impacts critical decision making, officer safety and the use of force.

Most officers today have some working knowledge and training in how various human and environmental factors impact officer safety, critical decision making and force option selection. Specifically, officers taking use of force/deadly force classes are taught how to deal with dangerous subjects they encounter who are armed with edged weapons. In 1983, then Salt Lake City PD Sergeant Dennis Tueller developed a training lesson to teach officers about the concept of “action – reaction perception lag time” and the “reactionary gap.” This important lesson, which teaches the formula of distance verses reaction time (D vs RT), now known as “The Tueller Drill,” is still taught in many use of force and firearms classes today.

Tueller’s principle demonstrated that a subject armed with a knife twenty-one feet away from an officer with their sidearm holstered, could easily engage and kill the officer before the officer could react, draw, aim and fire their weapon.[1] Remember that action is always faster than reaction.

A 20th Century U.S. Air Force fighter pilot, Major John Boyd, developed a combatives concept based on psychophysiology which he referred to as “The OODA Loop,” to teach fighter pilots how to better engage and defend against and destroy opposing pilots. OODA Loop is an acronym for Observe, Orient, Decide and Act.[2]

There is a large body of vetted, published research in the fields of psychology, physiology, biomechanics, vision, hearing, and physics which contribute to what we know about how the body reacts to life threats. This research informs us that when the average human experiences a life threat, the five basic responses are (1) defend (fight); (2) disengage from the threat (flee); (3) warn the threatening actor (posture); (4) become confused, panic and/or freeze; and (5) submit/surrender.

When humans experience what they perceive to be a life threat, the brain automatically engages the OODA loop. However, the brain first prepares the body for the threat by immediately and involuntarily dumping “survival chemicals” into the body. These survival chemicals are adrenalin (a powerful stimulant) and endorphins including dopamine which are pain blockers. These powerful chemicals can both help and hinder the body’s performance and its ability to survive an attack.

For instance, the stimulant adrenalin drastically increases the body’s BMR or basal metabolic rate, which is measured by respiration, heart rate and blood/fluids pressure. On the positive side, once adrenalized, the body’s actions can become faster and more powerful. The body can run faster, fight harder and its strength potential can rise exponentially. However, on the negative side, pressurized vitreous fluid in the eyes can change the shape of the cornea. This can cause depth perception problems and drastically reduces peripheral vision from 180º all the way down to 10º off of center. This sudden and extreme narrowing of the field of vision is referred to as “tunnel vision” or “an island within a sea of blindness.”

When your body responds to a life threat, the overproduction of adrenaline reduces blood flow to the ears,causing diminished or total temporary hearing loss. At the same time, the brain ignores less critical input to focus on visual stimuli. Obviously, not only can both circumstances significantly reduce the body’s ability to survive a deadly encounter, but they can negatively affect critical decision making, deadly force decisions and cause lapses in stress recall memory.

As I wrote in my 2014 article, “Revisiting the 21-Foot Rule, Forensic Fact or Fantasy,” once the body experiences a life threat and the brain engages the OODA loop, it takes time to move through its Observe, Orient, Decide and Act components. [3] Depending upon which research articles one reads, generally it takes between .55 and .58 second for the average trained officer or civilian to observe and orient (process) a life threat. Then it generally takes another .55 to .56 second for the brain to select which of the five basic options available the brain thinks that the body can perform to address the threat. Finally, the brain must tell the body to act and engage the plan. This also takes time and that’s the purpose of our research and this article. So by this time, you might be asking yourself, “What does all this have to do with knife throwing?”

This year I was doing background research on the combative art of knife throwing when I came upon Internet videos of knife throwing expert Matthew Dunn. I reached out to Matt to teach me how to throw knives and he graciously agreed. I traveled to Matt’s unique combat range in New Jersey where I received three days of excellent, intensive training, learning the challenging martial art of combat knife throwing. By the end of my second day I had learned how to accurately throw a specially designed ten inch Arvo fixed blade knife both underhand and overhand at single and multiple fourteen inch targets. By the end of my training, I had learned how to accurately center-punch a fast-moving attacking target coming straight at me.

Watching a trained expert like Matthew Dunn access and accurately throw deadly knives in the blink of an eye while monitoring my own progress, speed and accuracy after only two days gave me pause. Officers up against experienced subjects who can throw knives are at a serious disadvantage, even when unholstered and positioning their weapon in the low-ready position towards their adversaries. The OODA loop works against officers at close distances. In an effort to confirm my theory, Matt and I put applied sciences and human factors to the test to answer a hypothetical, “Which is faster, the gun or a knife in the hands of an experienced knife thrower?”

We first arranged single and multiple 14” stationary targets at distances of 8 and 12.5 feet and used a speed gun to clock the velocity of our throws. Next would be accuracy. We allowed only for solid, center-mass hits on a fourteen inch target. This would mean a knife striking only the eight, nine or ten rings which reduced the target size down to roughly ten inches. Hits within this area would be considered as “center-mass” hits. We conducted three hours of our experiments documented by video and photographs. The results were both astonishing and disturbing. Our combined efforts showed that unholstered with our hands behind us for underhand throws, or at the “ready” position for overhand throws, we could consistently strike targets center-mass at speeds of between 30 to 34 mph.

Returning to the published human factors research on experimental, timed “gunfight” and edged weapon, Tueller Drill-type scenarios, it has been generally documented that it takes a trained officer about 1.0 to 1.5 seconds to raise up from the “low ready” to the “on target” positions. It then takes that trained officer about .33 second to depress the trigger of a firearm.

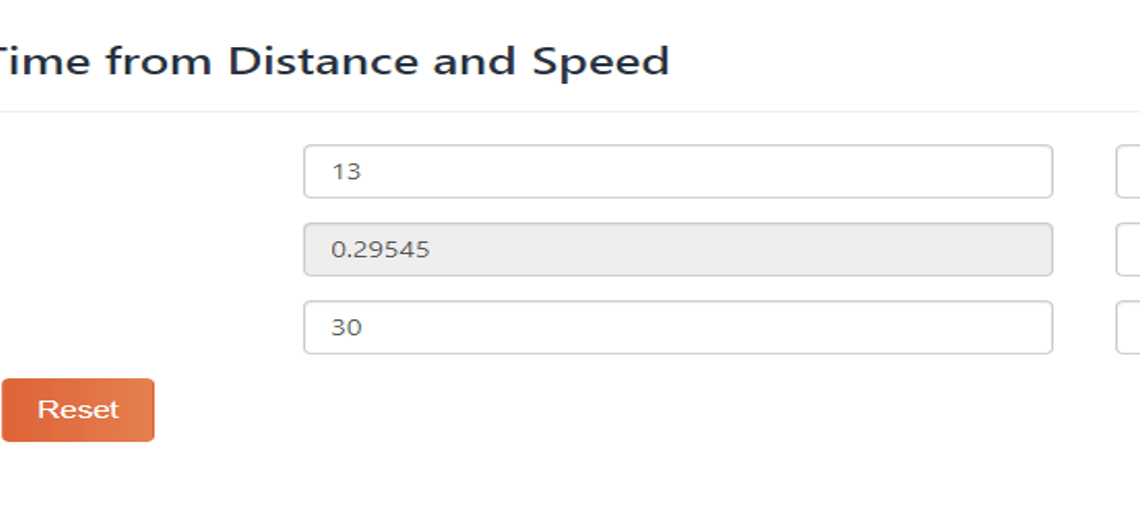

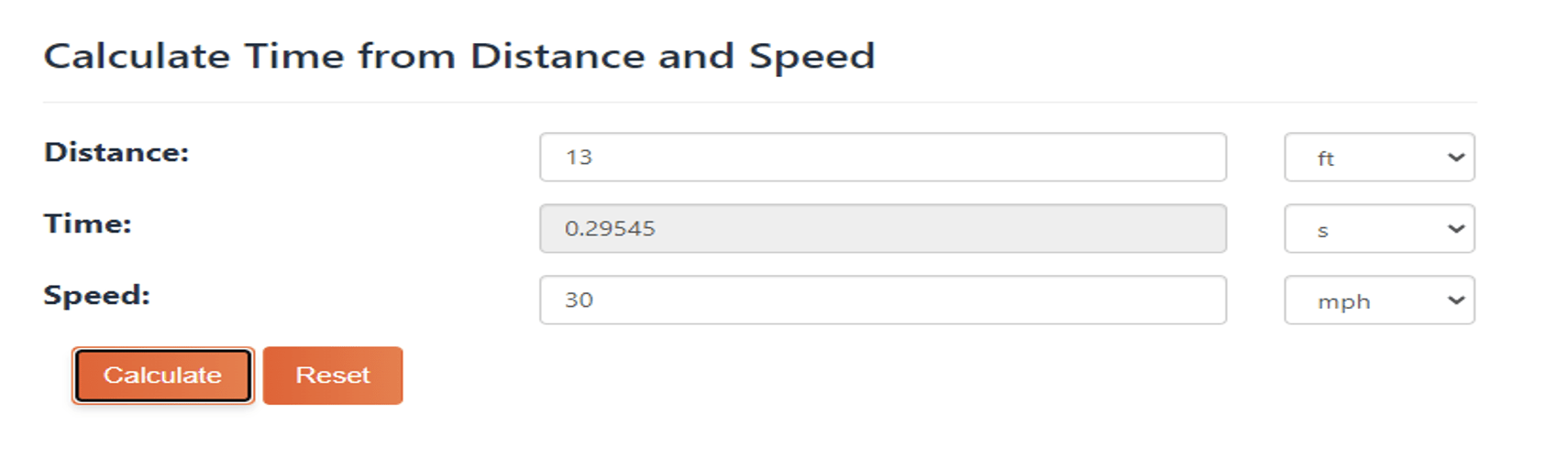

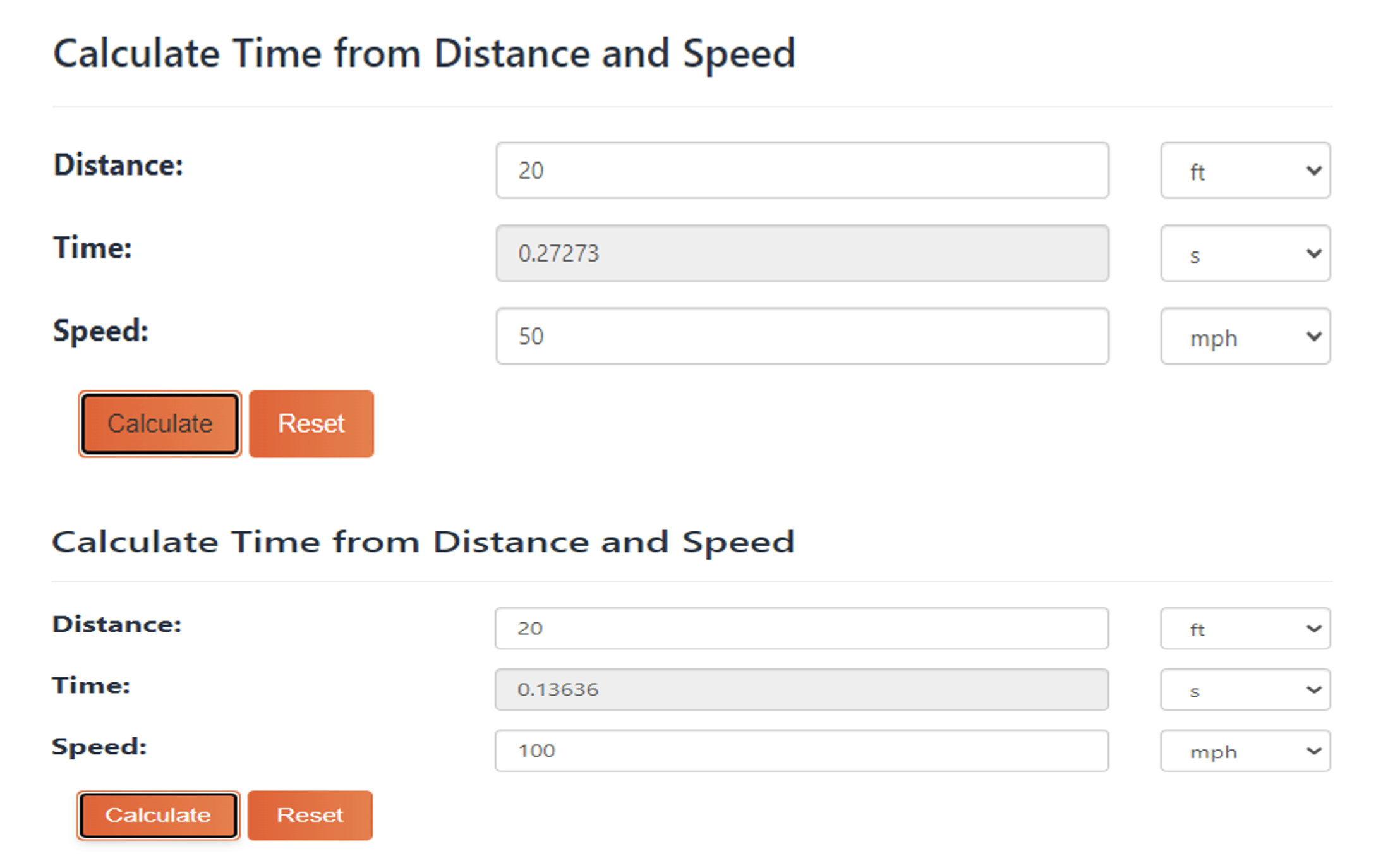

In our brief experiments, we found that we could access and deliver a 10” lethal missile traveling 30 mph from 13 feet away with point of delivery center-mass hit on target in only 0.29 second! At 30 mph, that knife is traveling at roughly 45 feet/second.

The following week after Matthew Dunn had studied videos of Major League Baseball pitchers throwing a fastball, he was able to mimic the biomechanics which then allowed him to greatly increase his knife throwing speeds to between 100 – 102 mph. At 100 mph, the knife is traveling to its target at 146.6 ft/per/second. If an officer was 13 feet away from the knife throwing assailant, the officer’s reaction time to depress the trigger of his handgun would have to be an impossible 0.088 seconds!

Continuing our knife throwing experiments, we found that a skilled knife thrower hurling a knife from a “reasonably safe” distance of 20 feet, at a speed of 50 mph or 73.3 feet/second can accurately strike the officer in 0.27 seconds. If the officer was 20 feet away from his assailant and the knife was thrown at a speed of 100 mph, the officer would have only 0.13 seconds to complete the OODA loop and depress the trigger of their handgun.[4]

The obvious danger to officers here is that even a trained officer with their gun pointed towards a knife yielding adversary with their finger on the trigger would not be able to complete the OODA loop before the subject armed with the knife could accurately throw his knife and strike the officer.

The obvious danger to officers here is that even a trained officer with their gun pointed towards a knife yielding adversary with their finger on the trigger would not be able to complete the OODA loop before the subject armed with the knife could accurately throw his knife and strike the officer.

In situations where an officer is holstered, as in a foot pursuit, and then suddenly encounters a fleeing subject who instantly turns around with a throwing knife in their hand, “Hick’s Law” engages, further slowing the officer’s reaction time. The officer is now faced to make an immediate “shoot – don’t shoot” force decision.

Hick’s Law is a psychological premise which teaches that the more options available to a person, the longer the decision making and action time it takes to respond. In the case of an officer, their thought (decision to action) process may be further impaired by considering department policy, disciplinary actions, criminal prosecution and/or civil litigation if they make the wrong decision. Once other distractions or impairments such as lighting, the physical environment, time, distance, and the presence of onlookers are added to the scenario, it is easy to see how quickly the officers finds themselves at a clear disadvantage against the knife thrower.

Even though our knife throwing human factors experiments have just begun, our work has raised some important tactical, officer safety, use of force and legal issues that we strongly suggest officers, trainers, police practices experts and agency defense attorneys consider.

- Always keep in mind the “Graham Standard” when evaluating your use of less-lethal or lethal force against a person with an edged weapon. Any use of force, especially deadly force involves an officer’s objective probable cause belief that the assailant poses an imminent threat of serious bodily injury or death to the officer(s) and/or others.

- Remember that distance is your friend. Longer distances equates to longer OODA loop reaction times. The further the distance you are from a person with an edged weapon, especially a throwing knife, the harder it will be for the knife wielding subject to accurately hit you. Experienced knife throwers can easily and accurately hit their targets out to 20 feet. When dealing with a subject armed with a knife, the minimum distance you should be from them is 40 feet if the environment allows.

- “Scoot & shoot.” When confronted by a knife thrower, once you detect an aggressive movement where you might have to respond with deadly force, always remember to move off the “X” as you shoot.

- If practical and available, seek and negotiate behind solid cover – something that will stop a heavy bladed knife.

- Be very careful about bringing an electronic control weapon, or any other less lethal weapon to a knife fight. Always consider that a person armed with a knife can not only engage and stab you but can now easily throw and accurately kill you with that knife at distances under 20 feet. These are the distances where ECW’s, OC and less lethal munitions are most commonly deployed. Rather, think about using a two-officer team with a 40 mm less lethal, multi-round impact munition, backed up by lethal force.

- Generally, absent a trauma plate, your body armor was never meant to repel sharp, heavy bladed, pointed throwing knives. Also, skilled knife throwers can easily strike targets where you have no body armor such as your head, stomach, groin and legs.

- Just because the subject with the knife is not holding the blade in an overhand attack posture does not mean that they can’t easily and accurately throw that knife underhanded or from a “side/slashing” throw handle. Pay close attention to whether the subject is holding their knife in a master grip (on top of or to the side of the back spine of the knife). The way the subject holds the knife can provide a clue as to whether or not they are experienced in throwing knives. (See photos)

- Foot pursuits are strongly discouraged unless absolutely necessary. Remember that when you are chasing after someone, you are significantly reducing your reactionary gap as well as your ability to visually assess the threat and successfully engage the OODA loop.

- Share this article with its findings with your command staff, use of force instructors and your department’s legal team.

The authors emphasize that our research into knife throwing, human factors and deadly force has just begun. We encourage constructive comments and are making a video catalog of our research available upon request.

Our thanks to Larry Nichols, nationally renowned law enforcement handgun instructor, retired SWAT commander Capt. Nick Gottuso, retired homicide Lt. Bob Prevot, use of force experts Jerry Staton and Brian Hill, and attorneys Robert Switkes and Mark Jarmie for peer reviewing this article.

About the Authors

Ron Martinelli, Ph.D., is a forensic criminologist, retired police detective, and a master use of force instructor with 35 years of experience as a federal/state courts law enforcement practices and use of force expert. Visit: www.martinelliandassoc.com, DrRonMartinelli.com and Email: [email protected]

Ron Martinelli, Ph.D., is a forensic criminologist, retired police detective, and a master use of force instructor with 35 years of experience as a federal/state courts law enforcement practices and use of force expert. Visit: www.martinelliandassoc.com, DrRonMartinelli.com and Email: [email protected]

Matthew Dunn, is a prominent expert within the knife throwing community. His knife throwing videos are found on YouTube.com at youtube.com/@throwstar, on Facebook at www.facebook.com/matthewdunn, and on Instagram.

Matthew Dunn, is a prominent expert within the knife throwing community. His knife throwing videos are found on YouTube.com at youtube.com/@throwstar, on Facebook at www.facebook.com/matthewdunn, and on Instagram.

References

- “How Close Is Too Close?” Tueller, Dennis, The Police Policy Studies Council, © 2004, pp. 1-3, http://www.theppsc.org/Staff_Views/Tueller/How.Close.htm

- “How Close Is Too Close?” Tueller, Dennis, SWAT Magazine, © March, 1983

- “OODA Loop,” Lewis, Sarah, TechTarget, The TechTarget Network, TechTarget.com

- “Revisiting the 21-Foot Rule – Forensic Fact or Fallacy,” Martinelli, Ron, Ph.D., The ILEETA Journal, Winter Edition, Vol. 5, pp. 78 – 80 © 2014

- “Performing under pressure: gaze control, decision making and shooting performance of elite and rookie police officers,” Vickers, Joan N., Lewinski, William, Human Mov Science, National Institute of Health, Epub. )7-31-2011; 02-21-2012 Vol. 1, pp. 101-117,

- “Duel Dilemmas,” MythBusters, Discovery Channel, 2012, Archived from the original on 02-02-2014;

- Cite – Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386 · 109 S. Ct. 1865; 104 L. Ed. 2d 443; 198

- http://www.discovery.com/tvshows/mymythbusters/dueldilemmas.htm

- YouTube – https://com/@throwstar

- https://www.facebook.com/reel/814953597013442

Share and speak up for justice, law & order…

[ad_2]