[ad_1]

Last year, I wrote here about the beta release by Casetext of a powerful search tool, WeSearch, developed using an emerging branch of artificial intelligence known as neural networks, that is remarkably adept at finding conceptually related documents, even when they contain no matching keywords.

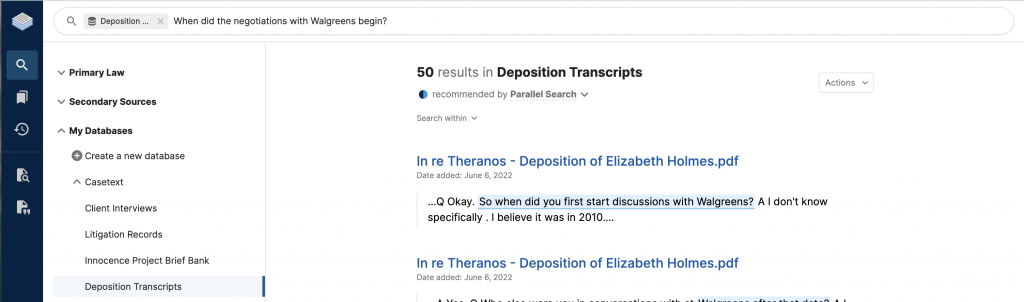

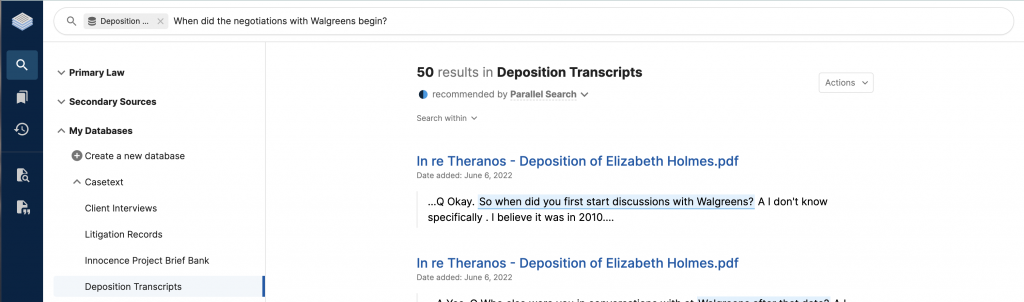

Now, Casetext is formally launching that search tool under a new name, AllSearch, and with a focus on helping litigators search large sets of legal documents, including for e-discovery or to search internal databases and repositories, such as brief banks, litigation records, deposition transcripts, and expert reports.

It is now also fully integrated with the Casetext legal research platform, so that a user can simultaneously search primary and secondary legal resources and their own document collections.

“I see this as the most important product launch in the history of the company by far,” Pablo Arredondo, Casetext’s cofounder and chief innovation officer, told me during a demonstration of AllSearch, “because I think it represents our ability to expand well beyond legal research and to bring all that Casetext is to all the other oceans of content out there that need it.”

Neural Network Framework

Before I say more about this new product, allow me to provide some background.

As I explained in that post last year, in 2020, Casetext launched Compose, a first-of-its-kind product that helps lawyers create the first draft of a litigation brief in a fraction of the time it would normally take.

A core component of Compose was Parallel Search, a powerful tool for finding conceptually related cases, even when they contain no matching keywords. As I wrote in another post, Parallel Search could be considered the secret sauce of Compose, using an advanced neural network-based technique to to follow you as you draft a brief and automatically provide you with conceptually relevant precedent.

What is remarkable about Parallel Search is its ability to go beyond the kinds of results you would expect from keyword searching, finding conceptually analogous caselaw even when the cases do not use the same language.

As Arredondo puts it, compared to Parallel Search, “what others called natural language search was just casual Fridays in the keyword prison.”

(I offer some examples of the power of Parallel Search in this prior post.)

It is based on transformer-based neural networks, the same general approach that underpinned Google’s open-source network framework developed by Google called Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers, or simply BERT. Casetext tailored the approach to make it work on the nuance and scale that litigation requires.

Proof of Concept

When Casetext launched WeSearch, it took that power of Parallel Search and extended it to virtually any collection of documents on which you might want to unleash it.

But it initially launched the product in beta only to select firms as a sort of proof of concept that this technology could be extended beyond case law to other types of document sets.

“The beta has been a very powerful validation for us of how this advantage of how you capture language — this ability to search by concept, not literal keywords — really can be applied essentially anywhere that lawyers are having to navigate lots of language, lots of documents, lots of text,” Arredondo said.

Among the beta users have been large firms that have used it in high-stakes e-discovery, and that have reported back to Casetext that they have been able to find critical evidence much earlier in the litigation.

Firms in the beta have also used it to search brief banks, transcripts, litigation files, SEC documents, contracts, and more, Arredondo said. Beta testers also included small and boutique firms, that used it to search through a complete litigation record or to process documents received through an FOIA request.

Now Fully Integrated

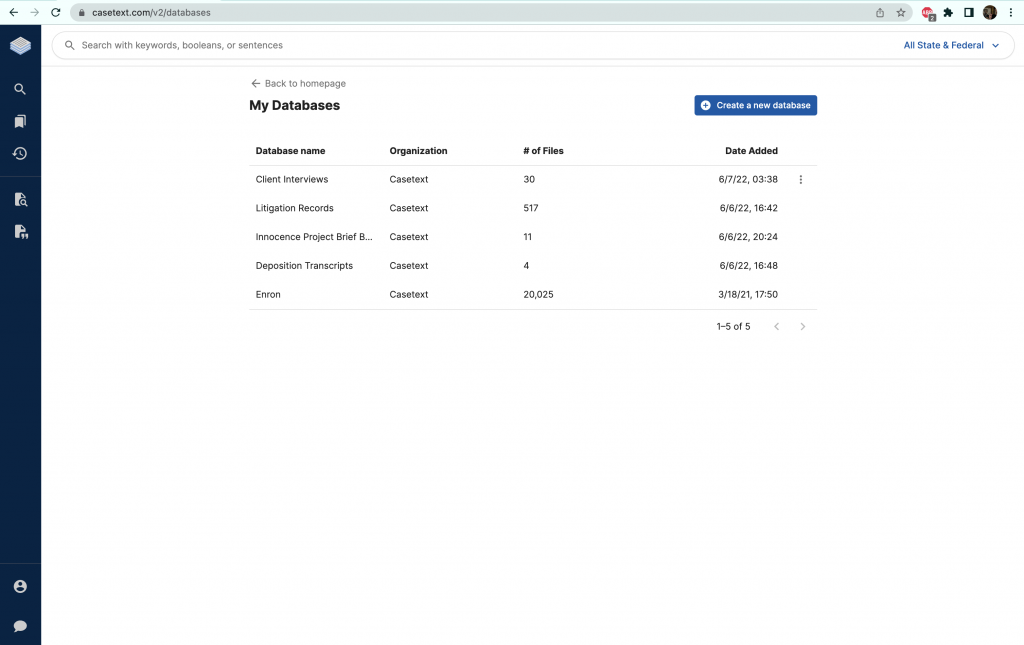

With this full commercial launch, AllSearch is now fully integrated within Casetext and appears as on option on the site’s home page. Users can upload any document set that they wish to search, and can create multiple databases of documents. For very-large document sets, a Casetext concierge can help with the upload.

Users can search both their own databases and legal resources, either simultaneously or selectively.

The largest set a firm has uploaded so far consisted of some 2 million documents.

Users can search any one of their uploaded databases, across several, or across both legal research sources and uploaded databases.

The price for this will vary with the subscription type, but will be based on per-gigabyte storage. Enterprise customers will have custom arrangements with Casetext, while smaller firm users will have a plan that starts with a gigabyte of storage.

Although I previously tested WeSearch, I have not yet had the chance to test this new release, which Arredondo said has been further refined for even more precise search results. I plan to test it soon and will post a follow-up when I do.

For Casetext, Arredondo sees this launch as the next step in the company’s evolution, towards offering an integrated system, driven by AI, where lawyers have access to everything they need.

“What we’re really excited about is getting all of the key information that an attorney needs in one area, and then applying the absolute cutting edge AI to it,” he said.

“For us at Casetext, that’s where we see ourselves going now, as being the best company to apply artificial intelligence to the complete information ecosystem, if you will, that a lawyer needs to work in.”

[ad_2]