[ad_1]

Ravish Kumar was born near the same Indian city – Motihari in Bihar – as George Orwell. In his early years as a TV journalist and nightly news anchor, Kumar did not imagine that he would live to be part of a modern-day Nineteen Eighty-Four nightmare. But that changed almost a decade ago with the election of Narendra Modi’s government in India. In the years since then, Kumar has become an increasingly lone voice of truth-telling in an Indian media landscape in thrall to the Hindu nationalist politics of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party (BJP). Kumar’s one-man campaign to maintain journalistic integrity, as mainstream news organisations became promoters of politicised fake news, earned him the “Nobel prize of Asia,” the Ramon Magsaysay award, in 2019. It also led to an unending campaign of harassment and death threats from government supporters.

Kumar, the Indian equivalent of, say, Jeremy Paxman in his prime, finally resigned from his post at NDTV in New Delhi last November, after the station was taken over by Indian billionaire Gautam Adani, a close friend of Modi. He now lives in virtual hiding with his family and broadcasts through a personal YouTube channel. His story, one of repression in modern India and of the existential crisis in truth-telling worldwide, is the subject of an urgently compelling documentary, While We Watched.

The director of that documentary, Vinay Shukla, tells me he knew he had to make his film when he turned on to watch Kumar’s news show back in 2018: Kumar interrupted the bulletin to berate his own viewers, telling them they had to start questioning the lies they were being fed, had to stop watching TV and look for information from other more reliable sources. “Most news presenters are always praising their audience, saying: ‘We are here to serve you’ and so on,” Shukla says. “Ravish, on the contrary, was chastising his audience, saying: ‘You’re the problem.’ I could see that here was an unusual protagonist – this huge figure in the [Indian] media – who has begun to wonder if the society for whom he is doing this work even cares for him any more.”

For the next two years, Shukla, who had previously made an award-winning documentary about the creation and struggle of an Indian opposition party, An Insignificant Man, essentially moved in with Kumar, filming him five days a week over that period. The result is an intimate portrait of a man struggling to preserve his conscience and freedom in the face of overwhelming hostility and political and commercial cynicism; a man trying, in Orwell’s terms, at 9pm every night, to tell the nation that two plus two actually equals four.

When I speak to Ravish Kumar himself on a long Zoom call, he describes himself now being “in exile” in his own country. He assumes our call is being monitored by his tormentors; before he joined it, he received the usual anonymous texts saying: “We will see you.” Once he left NDTV in November, he became “persona non grata” in Indian media, he says. He continues to try to get at the truth in the world’s largest democracy, researching and writing “about 8,000 words a day” for his YouTube broadcasts.

I wonder, looking back, when he first felt that things were falling apart? “It was June or July 2014,” he says. “I sensed that a kind of avalanche was coming in Indian media. At that time, many of my colleagues would say: ‘Well, power comes and power goes.’ And: ‘We have enough experience, Ravish, we have seen many leaders.’ But my gut was saying: ‘No, this is not something that has happened before. Something new is coming.’ In a very short span of time, the structures of newsrooms were demolished completely. That was not done step by step. It was done in one go.”

Shukla’s film contrasts Kumar’s meticulous efforts at reporting sectarian violence, or the desperate conditions in rural villages, with the shouty populist news channel Republic, which quickly became the Fox News of Indian media after Modi was elected prime minister. Republic’s excitable presenters are seen to fuel division and mistrust of the country’s minority (200 million) Muslim population, to routinely call political opponents of the BJP traitors, to promote warmongering against Pakistan and to neglect to report on the complex issues faced by ordinary Indians. In its manufactured culture wars and unhinged sloganeering, it is, you sense, the channel GB News aspires to be.

Now 51, Kumar, a history graduate, had by 2014 been at NDTV for 15 years, having risen from the mail room to become its most trusted and recognisable face. For a long time, the station supported his mission to call out what was happening elsewhere in the media. “NDTV started running a campaign that said: ‘We do not profit from hate,’” he says. “The owners were trying to save their core values. But in that process, everything became very tough. It was very tedious to always defend themselves.” Within the station, Kumar occasionally came under pressure to moderate his tone. “But if I said no to an editor,” he says, “they took it at once that this is my final word.”

Did it come as a shock to him how shallow the ethical foundations of much of the media proved to be? “I wasn’t shocked,” he says, “but I was very pained and deeply hurt that no one stood up to stop this. A lot of [journalists] started making adjustments and those adjustments led them into that room with no windows, only the voice of command, saying: ‘You have to do this.’ And that is what they did.”

The film records something of the inside story of that playbook of fake news that we have all witnessed happening in plain sight: the undermining of properly sourced information across social media, the seeding of conspiracy theories, the targeting of individual journalists and organisations. There were, and remain, pockets of resistance to this pressure, Kumar insists: “But the force of avalanche was such that nobody was untouched in their newsroom, whether he was a senior reporter or whether he was an intern.”

Kumar’s eventual resignation is referenced in the recent scathing Index on Censorship report into the escalating repression by Modi’s populist government. “It has the structures of democracy but it has weakened democracy’s functions… it has a media which is eager to demonstrate how nationalistic and patriotic it is in order to curry favour with the ruling party.”

That determination is fuelled in part by fear. Seven journalists are now in prison in India and many more have been subject to targeted harassment; eight journalists at the Wire website were charged with sedition in 2021 for reporting that the family of a protester, killed at an anti-government rally, believed he was shot by police. Other news organisations have been subject to blackouts, while some have been raided by police, including the BBC offices in Delhi and Mumbai, which appear to have been singled out after the corporation produced a two-part investigation into Modi’s alleged history in sectarian violence. India – the world’s most populous nation – has been consequently sliding down the UN’s human rights tables; among the top 10 nations that jails writers and journalists, it is the only “nominally democratic” one, according to PEN, the international charity that supports freedom of expression.

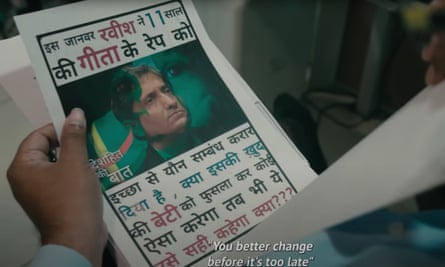

Shukla’s film examines the effect that the wider climate had on Kumar’s mental health. “I’m a very fearful person,” he insists, in the face of plenty of evidence to the contrary. “I had this strong feeling that I should not do anything immoral, but I wasn’t ready to handle that mental process. It destroyed me. When they launched [the continuous] attacks on me on social media, I could not handle it. I was very terrified, petrified. NDTV understood I needed security – but I also needed counselling. I stopped sleeping. I was awake all the time assessing the threat to my life and my family.”

In addition to the constant wave of texts and calls from people promising to cut his throat, Kumar was pushed around in the street while working. On one occasion he was chased down the road by men with clubs and iron bars, only just making it to his car. The family – his wife is an academic and they have two teenage daughters – stopped going out together; on the rare occasions they did, he would walk on the other side of the street so they would not all be subjected to any attack.

Watching all that again on Shukla’s film, he says, was almost too much for him to bear. “The first time, I had to shut my eyes because I could not see myself again, going through that process. My daughters haven’t watched it yet,” he says, “My wife saw it and she was very saddened too, but she’s a rational person. She said that people who watched the film would be able to see the story of any journalist, not just me.” He smiles a little ruefully. “The other thing I was surprised and amused about,” he says, “was that I finally saw what Vinay had been doing filming me for so many months and years. I used to tell him every day that my life was not exciting: who wants to watch a man get up from the bed and go to work?”

The director trusts that his story has a wider reference than that. “I think of the film,” Shukla says, “as my love letter to journalism, so that people understand, really, the price that proper journalists have to pay to be able to do their job. We are living in a time of disinformation. The dehumanisation of journalists is [part of that].”

Shukla is just about of the generation who came of age with social media. “I used to watch the news,” he says. “But it used to make me anxious all the time.” Much of that anxiety, he suggests, is built-in with the attention deficit structure of television news channels, which jump quickly between crisis and disaster and outrage. He has used the fast-cut techniques for his own film – but in order to dwell thoughtfully on a single life. “There are lots of quick cuts [in While We Watched] but I was hoping to have the opposite impact. If TV news is designed to desensitise you, I wanted to use the same form and sensitise people, to do the complete opposite.”

He sees an increasing desire for that kind of slowness and depth of inquiry among an emerging generation of Indian documentary-makers, who are using the form as a counterpoint to the noisy chatter of the mainstream media; presenting proper complexity as a political act. Kumar recognises that opportunity and is encouraged to be exhibit A in it.

“I hope that whoever watches this film will see that resistance is possible,” he says. In the film, he insists that even if one person witnesses the truth, then the political and sectarian lies cannot prevail. “I have a very deep sense of gratitude to the community of viewers who support me,” he says. “They offered me anything, from a car, to a house, to money, to food. We do not know how many journalists have sacrificed their lives around the world to save this profession. I hope this film brings a ray of hope that it is not easy to kill journalism.”

The film is released in the UK and the US this month. Shukla is working hard to get it shown in India, lobbying cinemas and streaming platforms, referencing the documentary awards it has won at the Toronto international film festival and elsewhere. Still, as Kumar says, the culture of fear is such that: “I can’t imagine that anyone is saying: ‘Bring your film, I will put your big poster for it on the front of my cinema hall.’” Even so, he suggests, he is confident that the film will be seen: “Lots and lots of people have been asking me how they will be able to see this film in India. Everyone should watch this film. Mr Modi should watch this film.”

Kumar is not hopeful that fundamental changes in the news media in India – equivalent to the dismantling of the BBC – can be reversed. The vested interests, including at his old channel NDTV, are now too great. The politically favoured billionaires have taken over.

There’s a point in the film where he suggests that “people don’t question what they see on TV”. Given some of the extremes of what they now see, does he imagine that they may start to question that more? “To destroy Indian democracy,” Kumar says, “Indian media destroyed itself first. And it’s now very difficult to change this, even if there is a regime change. The news anchors who are spreading hate lies will not go away overnight. This media will never return for democracy. That’s gone.”

He does believe, however, that politics may find a way to bypass those structures. “The problem with social media,” he says, “is that it is rarely getting first-hand information. In India – and elsewhere – we have seen that social media can run in parallel and [amplify] compromised mainstream media. For this reason, the political opposition in India is going for a lot of mass contact. Rahul Gandhi [the former president of the Indian National Congress party], for example, is constantly on the road. Rallies, meetings, travelling by bus, by car, on foot. I cannot give a deadline that next year’s election, 2024, will mark the sunrise of new democracy. But I can see that the force of those who believe in democracy is multiplying at a fast rate.”

How, I wonder, before he finishes our call, is that colonial son Orwell viewed these days in his home town? “There is a museum to him,” Kumar says. “But most people are not very aware. It’s funny, over the years, I started talking about Nineteen Eighty-Four in my various programmes. Recently, the book has been translated into Hindi, along with Animal Farm. When [Donald] Trump was elected in the United States, I remember that Nineteen Eighty-Four suddenly became a very popular book to read and to buy.”

Perhaps, he suggests, that appetite will also be awakened in India. If so, the film of his life makes the perfect primer.

[ad_2]