[ad_1]

ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

on Mar 23, 2023

at 4:27 pm

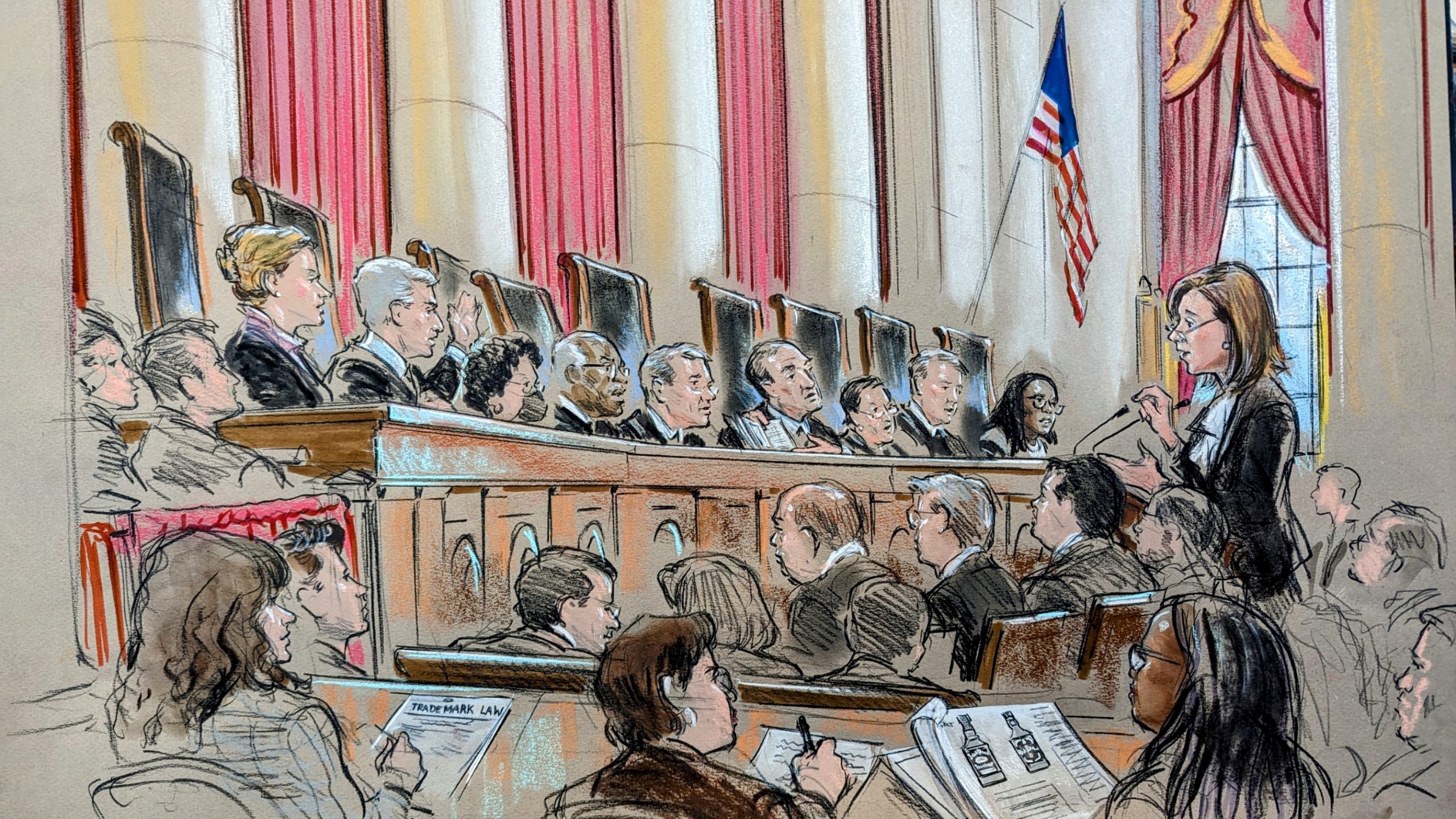

Lisa Blatt argues for Jack Daniel’s Properties. (William Hennessy)

As expected, Wednesday’s argument in Jack Daniel’s Properties v VIP Products showcased the justices grappling with line-drawing. At issue in the case was how First Amendment trademark principles should apply to a dog toy that pokes fun at Jack Daniel’s whiskey – a toy the size and shape of a Jack Daniel’s bottle, bearing a familiar-looking label that reads “Bad Spaniels” instead of “Jack Daniel’s.”

The case comes to the court from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, which held that the toy was protected under the reasoning of Rogers v. Grimaldi a 1989 ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit in a case filed by legendary movie star and dancer Ginger Rogers, who was seeking to block the use of the title “Ginger and Fred” by a movie about two fictional Italian cabaret performers. Specifically, the 9th Circuit reasoned that Rogers requires an exception to the trademark statute for expressive speech and that the “Bad Spaniels” dog toy fell within the exception. The problem for VIP Products, which makes the dog toy, is that almost none of the 9th Circuit’s decision discussed why anybody might want to tolerate the challenged toy. Rather, almost all of the argument focused on explaining how this intolerable parody differs from political or artistic works that Rogers and the First Amendment should protect.

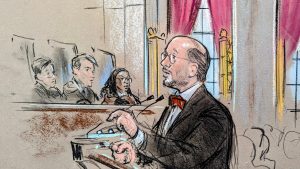

Bennett Cooper argues for VIP Products. (William Hennessy)

The problem for VIP was clear from the earliest moments of the argument, as Justices Elena Kagan, Ketanji Brown Jackson, and Sonia Sotomayor vied with each other to interrogate Lisa Blatt, representing Jack Daniel’s, about why this toy was unlike anything that Rogers should protect. Kagan suggested that the toy was “an ordinary commercial product using a mark as a source identifier. In that case, whatever we might think about the Rogers test, . . . [t]he Ninth Circuit just made a mistake as to this. The end. Why wouldn’t that be … the obvious or appropriate way to resolve this case if we were coming out your way?”

Kagan went on to explain that she was reluctant to abandon Rogers because there are other “cases which look really different from this case.” And in some cases, she noted later, courts “shouldn’t have to go through this whole analysis”; instead, they should be able to “can get rid of [them] in the first instance on a motion to dismiss without surveys, without a lot of fuss and bother.”

Kagan’s questioning of Bennett Cooper, representing the toy manufacturer, shows just how settled she was in her position by the end of the morning. The dog toy, she stressed, “is a standard commercial product.” “This is not a political t-shirt. It’s not a film. It’s not an artistic photograph. … Kagan acknowledged that “[t]here might be some hard cases. “But dog toys,” she concluded “are just utilitarian goods and you’re using somebody else’s mark as a source identifier, and that’s not a First Amendment problem.”

Jackson offered a slightly different formulation. She told Blatt that, in her view, “what you’re describing as the problem is courts grappling with the degree of expressiveness of various items in terms of determining whether or not this art, Rogers, exception should apply.” For her, it seemed to be a “cleaner, more consistent-with-the-statute way of looking at it … to ask, is the artist using this mark as a source identifier, as the threshold, and, if they aren’t, then I guess the Lanham Act doesn’t apply.”

Jackson seemed to embrace the idea that the Lanham Act, the federal trademark statute at issue, is addressing something of little concern to the First Amendment: “[T]he confusion we care about is that people in the marketplace are going to be looking at these items and think they are the mark owner’s because of the way they’re labeled.” Anything broader than that, she said, risks infringing on artists’ First Amendment rights.

Matthew Guarnieri, assistant to the solicitor general, argues for the United States. (William Hennessy)

Sotomayor was also hesitant to jettison the Rogers test. “What they’re trying to get at is whether the use of this trademark in this context … is confusing,” she said. When Matthew Guarneri, representing the federal government, began his time at the lectern, Sotomayor interrupted him almost immediately to say that because she “always ha[s] hesitation in doing away with something that circuits have been relying on,” she wanted his advice on the best basis for a narrow ruling.

That is not to say that the dog toy had no supporters at all. Justice Samuel Alito, for example, seemed completely unpersuaded that Jack Daniel’s faces any real-world risk of confusion, as he asked repeatedly whether “any reasonable person [could] think that Jack Daniel’s had approved this use of the mark.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch also appeared sympathetic to the toy manufacturer. He asked about the possibility of a remand, suggesting that “the district court may not have given adequate weight to the fact that this is a parody and the … differences in the label in its analysis.” When Cooper resisted a remand on that basis, Gorsuch quipped, “most lawyers don’t stand at the lectern and oppose a win.”

All in all, the argument strongly suggests a bench trying to avoid making any serious waves in First Amendment rules for political and artistic speech. It may take some time for all the justices to work through their preferred phrasings, and there well may be some separate writing. But it is hard to imagine a group of five coalescing to reject Jack Daniel’s plea for protection.

[ad_2]