[ad_1]

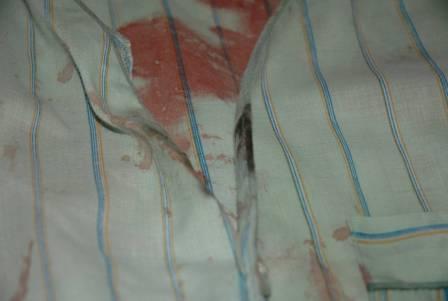

Shots fired from close range often leave tell-tale marks called stippling, or tattooing. Evidence of contact with hot gunpowder can be seen just above and to the sides of the “V” opening of the shirt (the soot-blackened area) in the photograph below.

The person who wore this shirt was the victim of a shooting at close range—less than a foot away—with a 9mm pistol. Notice there’s no hole in the back of the shirt. No hole, no exit wound. The bullet remained lodged inside the body, even from a shot at this short distance.

The section below contains a photograph of an actual gunshot wound (post autopsy).

*WARNING. REAL GUNSHOT WOUND BELOW – GRAPHIC *

*

*

*

*

*

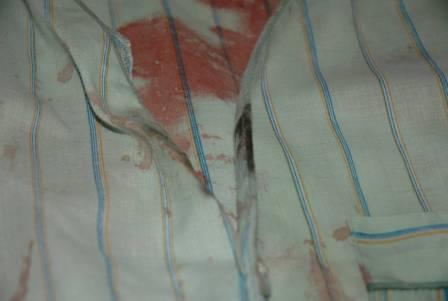

In the picture below, the hot bullet entered the flesh leaving a gray-black ring around the wound. The tiny black dots are the stippling, or tattooing.

Close contact gunshot wound to the chest.

The impact of the bullet and gases striking the tissue also left a distinct bruising (ecchymosis) around the wound. Notice the stitching of the “Y” incision. The incision is at the centerline of the chest. I took this photo during the autopsy of the murder victim.

The wound is round and neat and it’s approximately the diameter of an ink pen. It’s not like the ones we see on television where half the guy’s body is blown into oblivion, or beyond, by a couple of bullets from a hero’s gun.

Stippling

Stippling is due to burned and unburned powder grains exiting from the firearm causing pinpoint blackened abrasions on the skin.

For Every Action There’s an Equal and Opposite Reaction

Bullets don’t always stop people. I’ve seen shooting victims get up and run after they’ve been shot several times. And for goodness sake, people DO NOT fly twenty feet backward after they’ve been struck by a bullet. Instead, they fall down and bleed. They may even moan a lot, or curse. That’s if they don’t get back up and start shooting again. Simply because a suspect has been shot once or twice does not mean his ability, or desire, to kill someone is over, and that, writers, is why police officers are taught to shoot until the threat is over.

The bank robber I shot and killed during a shootout fell after each of the five rounds hit him. But he also stood and began firing again after each of my bullets struck—one to the head and four to the center of his chest area. After the fifth round he stood and charged officers. Four of the five rounds caused fatal wounds. Yet, he still stood and ran toward officers. I and a sheriff’s captain tackled and cuffed him. In another instance, a man engaged in a gun battle with several officers. He was shot 33 times and still continued walking toward officers.

Always keep Sir Isaac Newton and his Third Law of Motion in mind when writing shooting scenes. The size of the force on the first object must equal the size of the force on the second object—force always comes in pairs.

Entrance Wounds

Entrance wounds caused when rounds are fired from a distance (not close contact wounds) typically exhibit a hole that’s near the size and round shape of the projectile/bullet. These wounds typically lack stippling (see “stippling” below).

Sometimes entrance wound shapes are irregular because bullets may tumble during flight, instead of spinning.

Irregular entrance wound

Gunshot wounds caused when the weapon is fired from an intermediate range may present a wide area of stippling and are without a muzzle imprint and/or laceration. The area of stippling present depends upon the proximity of the muzzle and the victim.

Several factors that affect how much or how little gunshot residue (GSR) appears on a victim’s skin and clothing. For example:

- distance between the muzzle and victim when the round is fired

- angle of the gun barrel in relation to the victim

- type of clothing worn by the victim

- components of the gunpowder

- and more

Exit Wounds

Sometimes exit wounds are nearly as small or equal to the size of the entrance wound. The amount of damage and path of travel through the body depends on the type ammunition used and what the bullet struck as it makes it way through the body. However, they typically do not display signs and evidence associated with entrance wounds—imprint of the muzzle, stippling, or blackening of the skin edges.

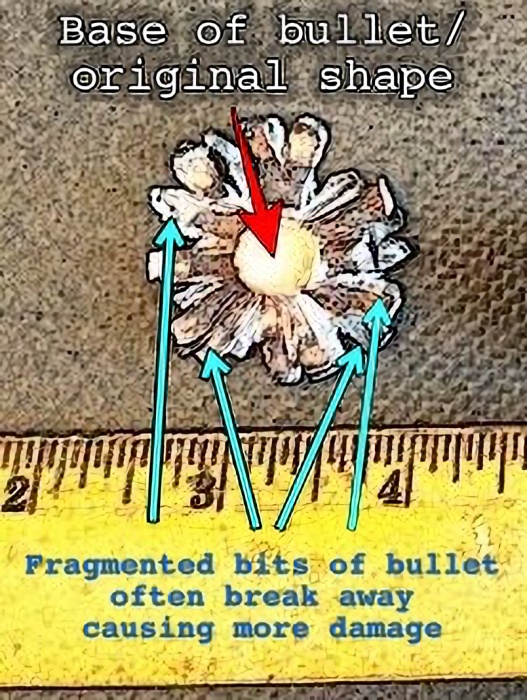

Many bullets, such as those used in hollow point ammunition, are designed to hit a target and remain within that target/body without exiting. When a hollow point round hits a target, the nose of the bullet expands and flattens, creating a larger surface area than the bullet’s original size. This helps slow and even stop the forward motion of the bullet while inside the target. The purpose is to prevent the round from continuing through the target and hitting something else. Still, exit wounds do occur, especially when the round strikes only soft tissue, or when the rounds are loaded with an amount of powder that’s more than what’s needed, making those rounds overly powerful.

Hollow point rounds expand and flatten when striking objects

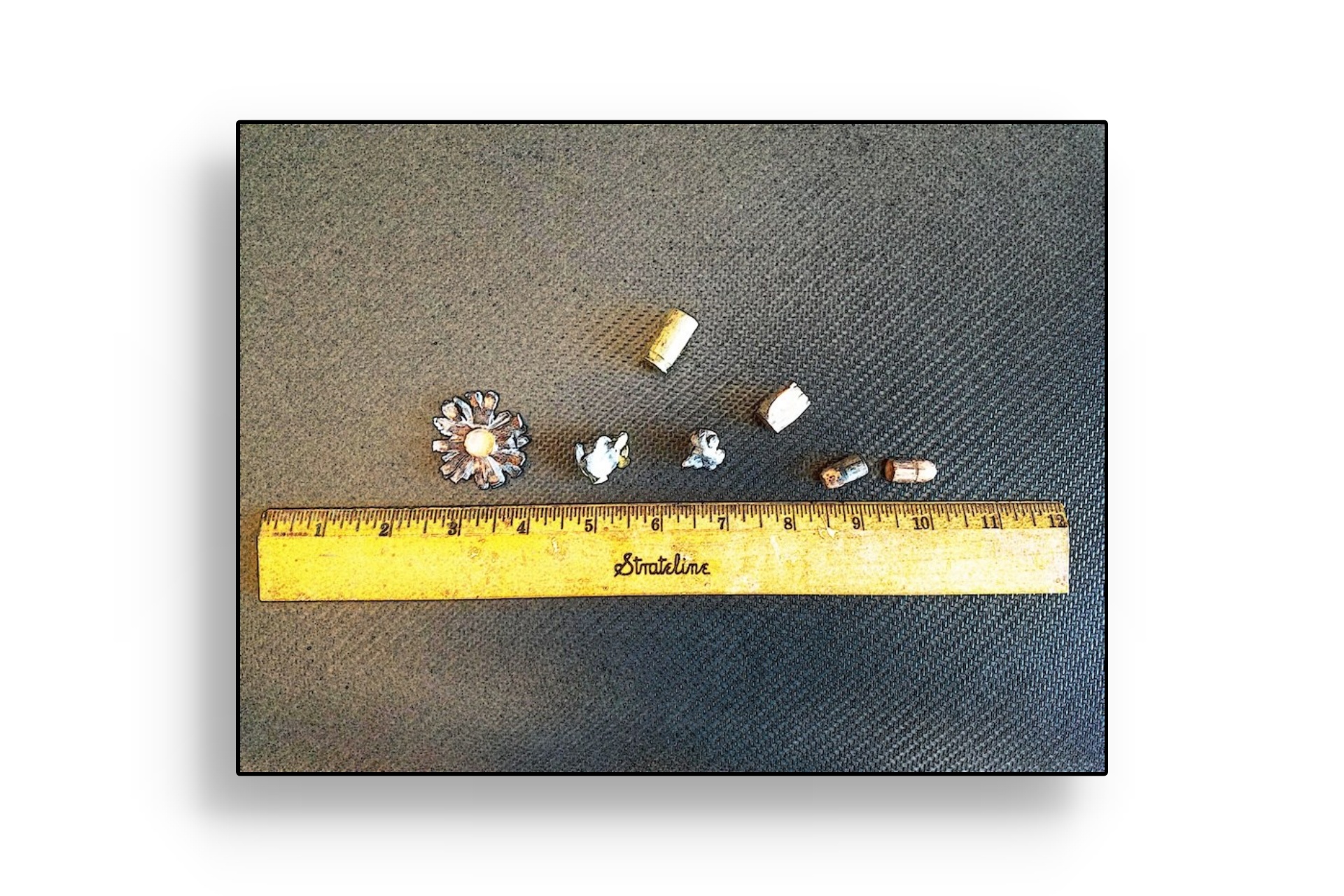

Below are other rounds we recovered after they’s struck hard surfaces at various angles. All were fired from the same gun. The flattened round on the left struck a steel surface head-in. To show the difference between striking a hard surface as opposed to something soft, the bullet at the far right was fired directly into a massively thick pile of foam rubber. It maintained its shape. The object at the top of the photo is an ejected brass casing. I took the photo at law enforcement firing range during a controlled exercise.

When a fired bullet enters a person’s skin, the tissue is instantly and forcefully dislocated outward from the center of the wound. The force is so great that the hole is, for a brief time, larger than the diameter of the bullet. However, skin is often elastic enough to reverse the action and draw the wound closed to a point where it’s sometimes smaller than the size of the bullet. This action totally dispels the fictional cops who, upon merely looking at a homicide victim’s bullet wounds, claim to instantly know the caliber of the bullet that caused the injury.

Exit wounds normally present pieces of avulsed flesh angled/beveled slightly away from the wound. Typically, there’s also no trace of gunshot residue around the outside of the wound.

Contact wounds occur when the muzzle is pressed against the skin when the weapon is fired

Contact wounds caused by the barrel of a gun touching the skin when the weapon is fired may present the imprint of the muzzle. The wounds sometimes show an abrasion ring (a dark, blackened circle around the wound) that’s caused as the hot gases from the weapon enters the flesh. The force of the gas blows the skin and tissue back against the gun’s muzzle, leaving the circular imprint.

- In areas of “loose” skin, such as the abdomen or even the chest area, wounds likely present as circular with blackened, seared skin surrounding the wound opening.

- On the head, entry wounds often appear as round punctures, again with blackened, seared skin surrounding the wound opening.

- Contact entrance wounds routinely exhibit soot on the skin surrounding the injury, and sometimes even laceration of the skin due to consequences of expelled gases from the firearm.

Near-contact wounds are caused when the muzzle of the gun is held a short distance from the skin. These wounds generally present as circular with blackened and seared edges. However, the searing and blackening cover a wider space than seen with contact wounds

Entrance and Exit Wounds in Bone

Entrance wounds in flat bones such as the skull are often round and show internal beveling in the direction of the bullet’s path. The shape and nature is quite similar to that of a cone.

Exit wounds in bone are most likely more irregular in shape than entry wounds and may show external beveling (a reverse cone), the opposite effect of the entrance wound.

[ad_2]