[ad_1]

U.S. law enforcement deals with a deficit of bomb-sniffing canines

The fallout from the global pandemic continues to crop up in some of the most unexpected scenarios, such as the shortage of bomb-sniffing dogs in the United States. Traditionally, federal, state and local law enforcement organizations have outsourced the breeding and early training of animals for this highly specialized K-9 job. According to the American Kennel Club (AKC), at least 80% of detection dogs are recruited from overseas, especially from Germany and the Netherlands. Although experts in the field had been alerting federal lawmakers to the disadvantage of importing such a disproportionate number of dogs for years, the disruption to supply chains during COVID-19 lockdowns and afterward further exposed the vulnerability of this practice.

“As more and more countries are realizing the benefits of having these explosive detection dogs, there is a greater demand. And there’s only a limited number of dogs that could be sustained in the programs that are there,” Cindy Otto, executive director for PennVet Working Dog Center at the University of Pennsylvania, told NPR.

A recent report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) tallied approximately 5,100 working dogs with three federal agencies and another 420 serving the government via contracting organizations. For bomb-sniffing duties, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) are the largest federal employers of detection dogs. They canvas busy public venues, such as stadiums and airports. The data did not include bomb-sniffing dogs employed by state, county or city agencies.

“The canine nose is the best technology we have for locating explosives, so we need to have a very consistent and high-quality source of dogs,” Sheila Goffe, AKC vice president of government relations, commented to Wired magazine.

However, the disruption to the supply chain means fewer newly trained canines available. Thus, the existing ranks must assume greater workloads. But the strenuous tasks these K-9s tackle generate concerns for the aging population of dogs. The GAO report states, “Working dogs might need the strength to suddenly run fast, or to leap over a tall barrier, as well as the physical stamina to stand or walk all day. They might need to search over rubble or in difficult environmental conditions, such as extreme heat or cold, often wearing heavy body armor. They also might spend the day detecting specific scents among thousands of others, requiring intense mental concentration. Each function requires dogs to undergo specialized training.”

Even before COVID, several U.S. universities established breeding and training programs to create a domestic pipeline, including Johns Hopkins Advanced Physics Laboratory, Auburn University and Gallant Technologies. The AKC’s Patriotic Puppy Program educates American breeders on the detection dog criteria. While many in academia express hopefulness that these efforts will shift sourcing and relieve some of the shortages, most initiatives are in the early stages. It could be years before law enforcement agencies can recruit their graduates.

“There is not yet a road map to a complete solution to domestic sourcing for detection dogs, but what we are trying to do is establish best scientific practices — everything from making sound genetic decisions about the breeding of detector canines to their development as puppies to how early environment affects their lifelong potential,” Skip Bartol, associate dean of research and graduate studies at the Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine, told Wired.

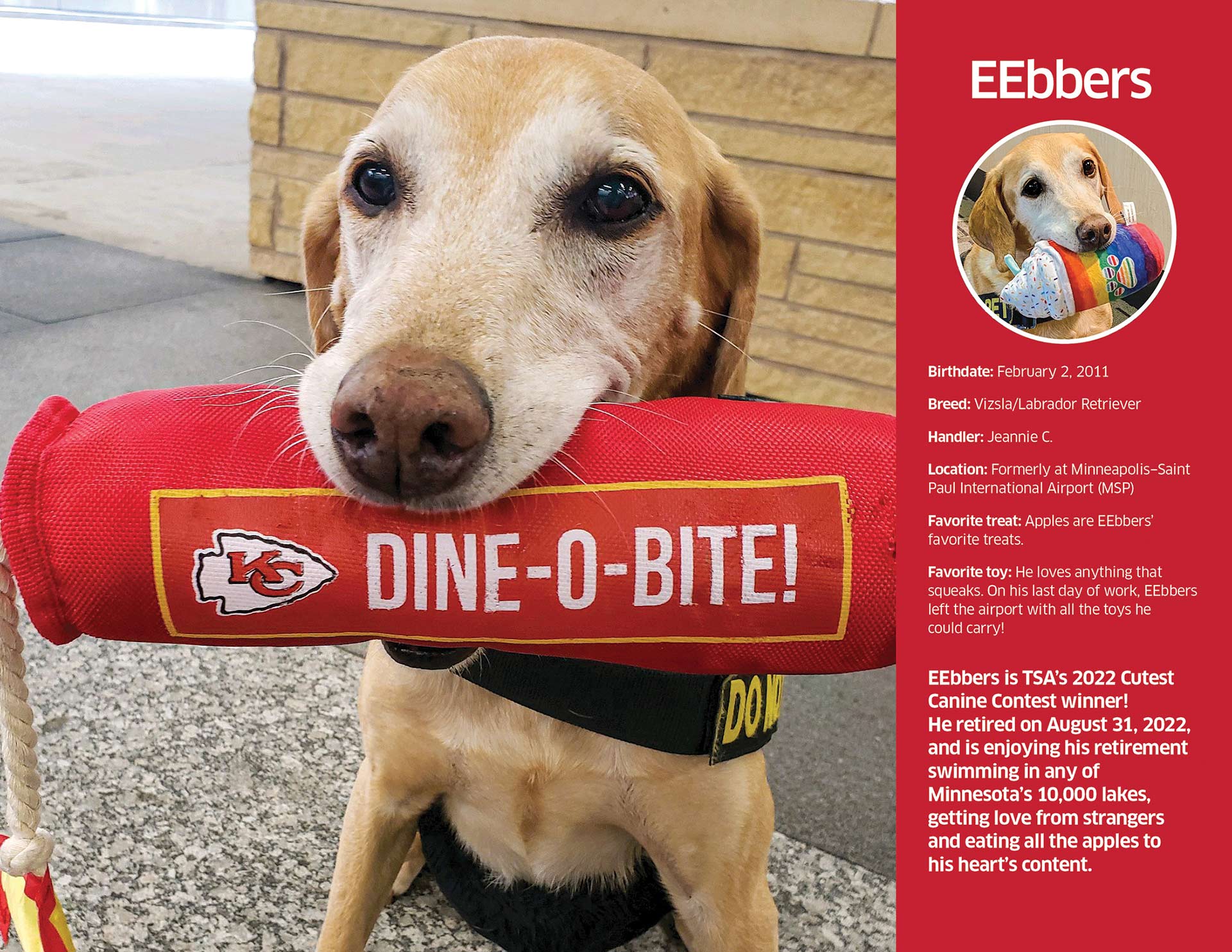

Calendar canines

You can show your support for the hardworking bomb-detecting dogs of the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) by downloading the free 2023 TSA Canine Calendar, featuring 13 of the force’s most adorable and dedicated four-legged members, at tsa.gov/sites/default/files/tsa_canine_calendar_2023.pdf. Cover model Eebers is doubly distinguished: Not only did he win the TSA’s 2022 Cutest Canine Contest, but at age 11, he was also the TSA’s oldest K-9 when he retired from patrolling the Minneapolis–St. Paul Airport earlier this year.

[ad_2]