[ad_1]

It has been a long two weeks for the Supreme Court. Since the leak of Alito’s opinion in the Dobbs abortion case several of the Supreme Court Justices have come forward offering their thoughts on the leak.

It has been a long two weeks for the Supreme Court. Since the leak of Alito’s opinion in the Dobbs abortion case several of the Supreme Court Justices have come forward offering their thoughts on the leak.

According to the Washington Post, “Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. called the leak ‘absolutely appalling.’ The Supreme Court issued a news release calling the leak a ‘betrayal of the confidences of the Court.’”

Justice Thomas later said in an interview “I do think that what happened at the court is tremendously bad. I wonder how long we’re going to have these institutions at the rate we’re undermining them and then I wonder when they’re gone or destabilized what we will have as a country and I don’t think the prospects are good if we continue to lose them.”

Justice Alito was more tight-lipped in his response saying, “The court right now, we had our conference this morning, we’re doing our work. We’re taking new cases, we’re headed toward the end of the term, which is always a frenetic time as we get our opinions out.”

Because of the leak, several journalists asked the question “is Roberts losing control of the Court”? An article from the Associated Press, for example, led with the question, “It’s Chief Justice Roberts’ Court, but does he still lead”? In an article for CNN, Joan Biskupic offered, “At this moment in his Supreme Court stewardship, John Roberts appears suddenly ineffectual. Gone is the confident jurist whose views prevailed across the board and the man who was all-controlling of operations at the court building.”

It wasn’t too long ago when Justice Kennedy retired and Roberts was touted as “[t]he most powerful chief justice since John Marshall.”

Such headlines quickly vanished when Justice Ginsburg passed away and the much more conservative Justice Barrett filled her place on the Court. Barrett and the other four conservative justices have now put their stamp on the Court, especially if the Dobbs opinion remains substantively unchanged and proves to overturn the Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade.

Of course, some are of the view that the Chief Justice’s role really isn’t to control or to direct the Court toward a common goal. Politico reported former University of Pittsburgh Law professor David Garrow’s view that “This isn’t the Army chief of staff. It’s one of nine and you’re more an equal than a superior…The power of the chief justice is a power of persuasion. Period.” Garrow continued by saying, “Anybody who says Roberts has lost control of the court simply doesn’t know any Supreme Court history because there have been plenty of chief justices who did not control the court.”

This article looks at the question of if Roberts was ever really a justice in control of the Court. If not, then the narrative of Roberts’ fading power loses much of its luster. Power is difficult to evaluate in a vacuum though and so it is far easier to evaluate Roberts’ performance by comparison to that of the previous Chief Justice, William Rehnquist. Through this comparison we can evaluate Roberts’ relative power when compared with his more conservative predecessor.

Much of what makes a justice powerful is what they can do to influence the Court’s most important decisions. During both Rehnquist’s and Roberts’ role as chief, many of the most important cases have been decided by 5-4 votes. These include Texas v. Johnson, Lawrence v. Texas, Bush v. Gore, Citizens United v. FEC, Shelby County v. Holder, and Obergefell v. Hodges. Much of this analysis accordingly looks at the chiefs’ roles in 5-4 decisions.

First a look at the difference between the chiefs. Roberts clerked for Justice Rehnquist and so he was exposed firsthand to Rehnquist’s decision-making. One might suppose from this background that Roberts would be a similar chief to Rehnquist.

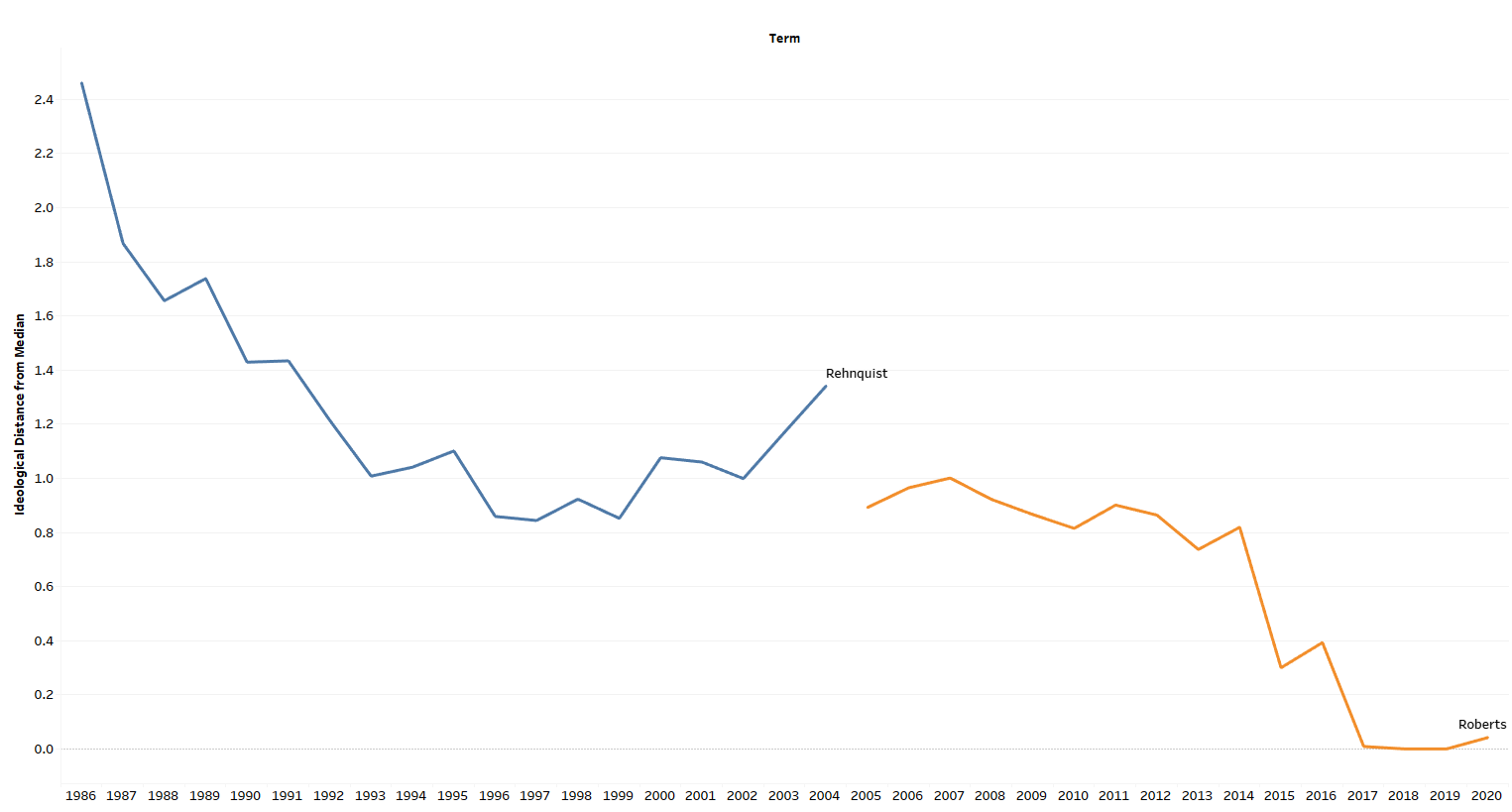

Looking at their relative voting patterns though Roberts appears far less conservative than Rehnquist. The Martin-Quinn Scores were developed to measure ideology across Court eras so that we can say, for instance, whether Rehnquist was more conservative than Roberts without their ever having worked on the Court side by side. This might be viewed as an imperfect measure as the justices differed on each Court as did the cases.

Assuming that ideology can be captured by looking at the other justices a given justice votes alongside, these scores can provide evidence of a justice’s relative preferences. If we look at ideology from 1986 when Rehnquist became chief through the 2020 term, we see that Rehnquist’s ideology was almost always more conservative than Roberts’.

Roberts was also the fourth most conservative justice until Justice Scalia passed away and then with the addition of Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett, Roberts fell to the sixth most conservative justice on the Court. Rehnquist on the other hand was the most conservative justice on the Court when he became chief, then the second most conservative justice when Scalia surpassed him in 1990, and finally became the third most conservative justice in 1991 when Thomas was confirmed. This ordering lasted for the remainder of Rehnquist’s career on the Court.

The median justice is oftentimes seen as the most pivotal justice on the Court. This justice can direct much of the Court’s decision making, mainly because this justice is the tiebreaker in many votes where the other justices are divided 4-4. The closer one justice is to the median, the more likely the justice will have a decisive vote in cases as the outliers generally have more extreme views that are sometimes out of sync with the Court’s majorities.

When Roberts’ and Rehnquist’s ideology scores are compared with those of the Court’s median member, Roberts is closer to this point for almost his whole career so far on the Court. The distance is measured in absolute terms so that all distance is shown as positive.

With Roberts’ closer distance to the median justice compared with Rehnquist’s one might surmise that Roberts would have a greater role in affecting outcomes in the most significant cases the Court hears.

How can we measure this? Garrow’s quote above about the chief’s lack of institutional power leaves out one important feature — the chief justice’s majority opinion assignment power.

When the chief justice is in the majority, the chief gets to select the majority opinion author.

In his University of Pennsylvania Law Review article, Strategy and Constraint on Supreme Court Opinion Assignment, Paul Wahlbeck wrote, “The power to assign authorship of the Court’s opinion provides the Chief with the capacity to direct the Court’s policy-making agenda. This assignment power is unique among the Chief’s duties in its ability to shape the development of the law.”

Later in the article Wahlbeck also wrote, “First, by selecting who will draft the majority opinion, the Chief Justice can direct which policy alternatives will receive consideration by the Court.”

With fewer constraints, a chief will assign the bulk of the decisions, as the chief only does not assign when he is in dissent. Roberts (through the 2020 term) and Rehnquist both assigned 65% of their respective Court’s 5-4 majority opinion authors.

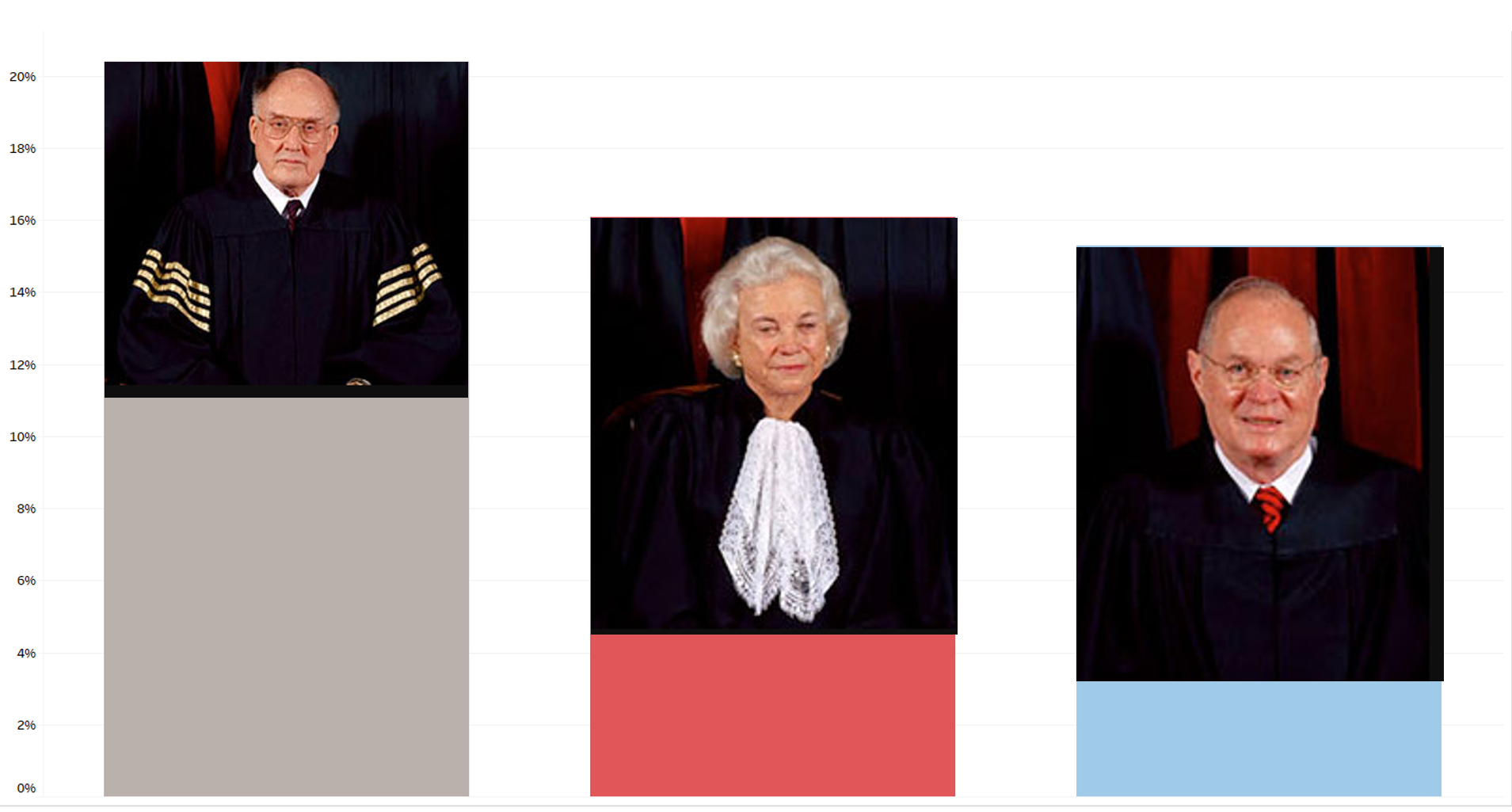

When we look at Rehnquist’s most frequent assignments with 5-4 majorities, we see that he assigned 21.5% to himself, 16.9% to Justice O’Connor, and 16.1% to Justice Kennedy.

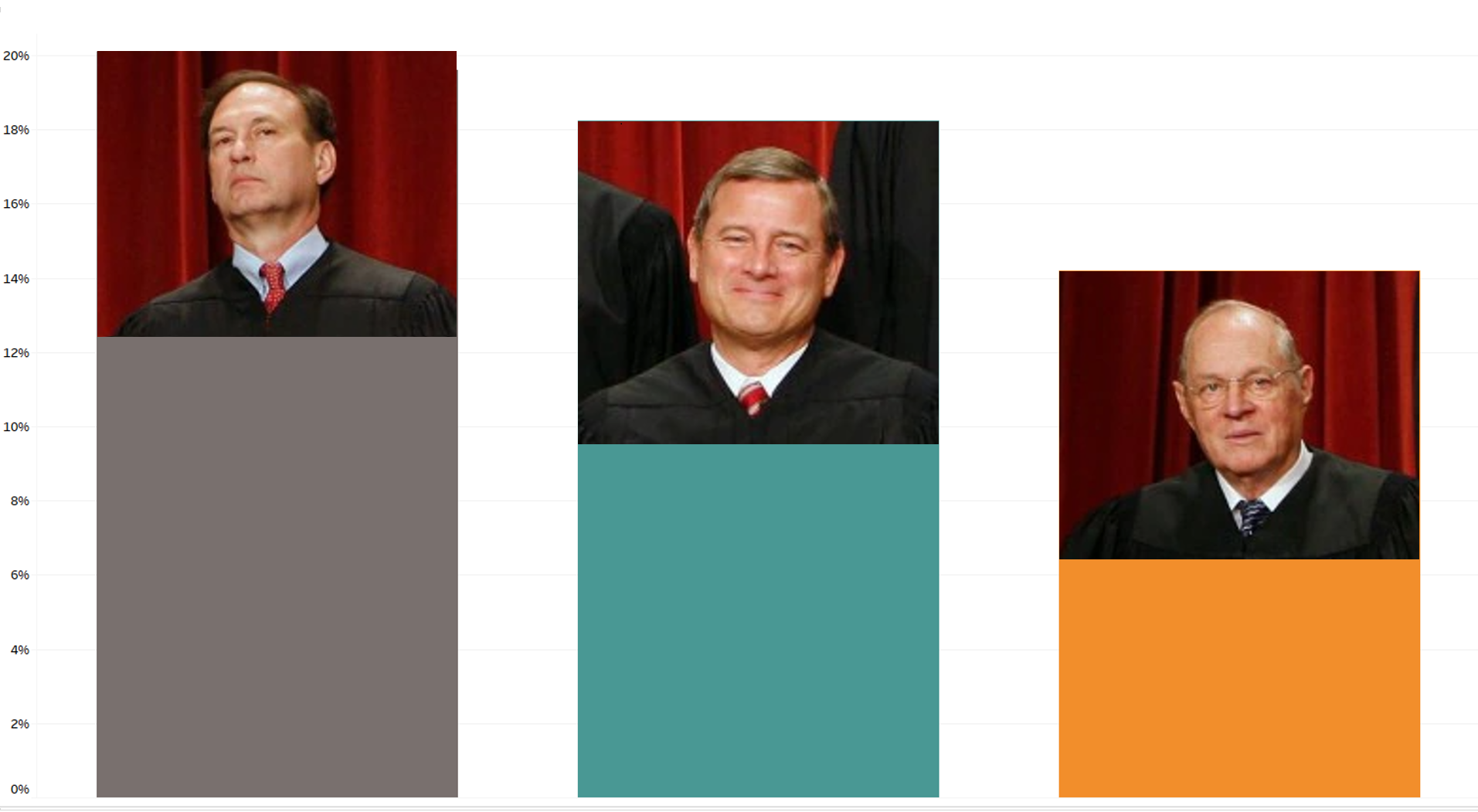

In a piece for the Atlantic after the Dobbs opinion was leaked, Molly Jong-Fast wrote, “It’s not the Roberts Court anymore — it’s the Alito Court.” The data on the Roberts’ Court shows that Roberts delegated quite a bit of power to Justice Alito throughout his tenure as chief. Looking at Roberts’ assignments in 5-4 decisions, Alito is the justice the chief assigned to most frequently.

Through the 2020 Term, Roberts assigned 20.3% of opinions to Alito, 18.9% of opinions to himself, and 14.7% of opinions to Kennedy. Adding in the fact that Roberts’ ideology as conveyed by his votes is less conservative than Rehnquist’s, this would suggest that Rehnquist wielded more power as a chief than Roberts did.

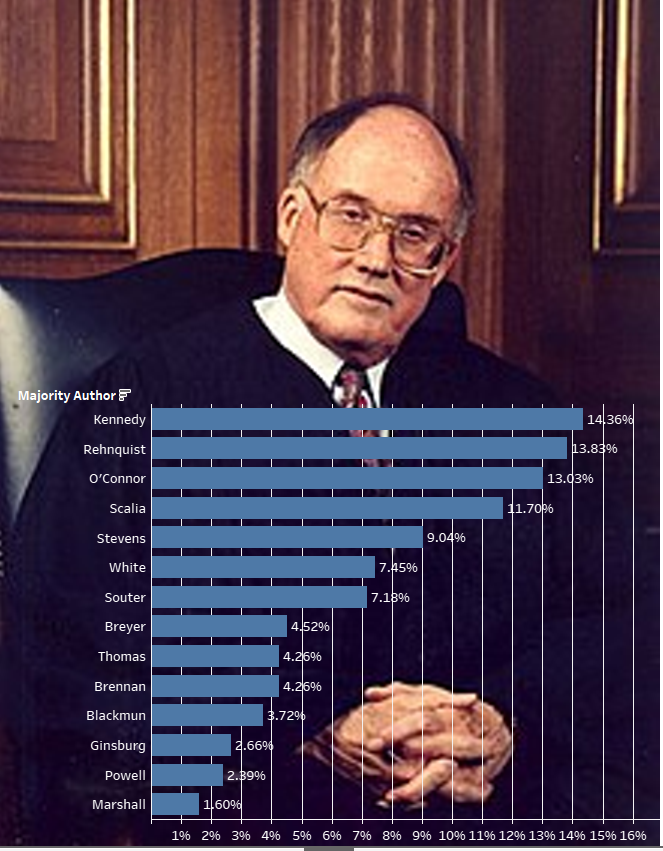

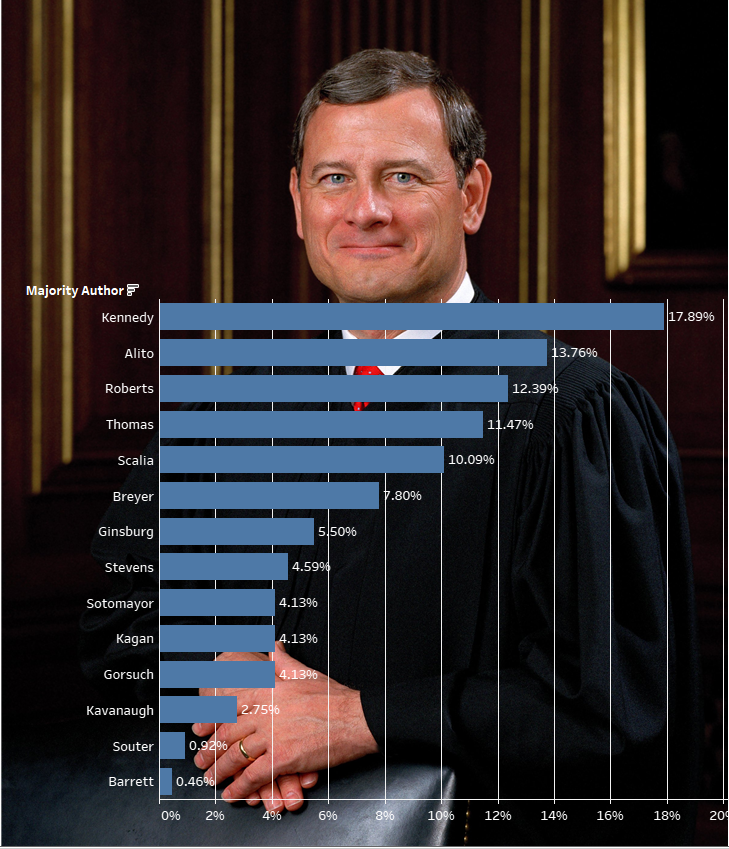

Another way to put this comparative power under the microscope is by examining which justices authored the most decisions in 5-4 cases during the Court Eras. Here we see Kennedy’s staying power across both Eras, but also that Rehnquist was able to retain majority authorship much more frequently than Roberts.

From the Court’s 1986 Term through the 2004 Term, Kennedy authored 14.4% of 5-4 decisions while Rehnquist was close behind with 13.8% of decisions, followed by O’Connor with 13%.

Kennedy’s rate of authoring 5-4 decisions under Chief Justice Roberts far exceeded his rate under Chief Justice Rehnquist.

Kennedy authored 17.9% of 5-4 decisions under Roberts, followed by Alito with 13.8%, and Roberts with 12.4%. If we refocus on the 2005 through 2017 Terms under Chief Justice Roberts since Kennedy retired at the end of the 2017 Term, Kennedy authored 21.4% of five-to-four decisions, Alito authored 14.3%, and Roberts authored 12.1%. Kennedy’s increased role in these cases relative to the other justices likely diluted Roberts’ influence in this area.

Part of the reason why Kennedy so effectively leveraged his influence in both Court Eras is that he was so often the fifth and decisive vote in decisions where the other justices split 4-4. Until Kennedy retired, Roberts seldom took on this role, which meant he was a solid conservative vote, but could not force a close vote in the conservative direction without Justice Kennedy.

Between the 2005 and 2010 Terms, a conservative justice sided with the four more liberal justices on 20 occasions. In 16 of those instances, Kennedy was the swing justice, Scalia was the swing justice twice, and O’Connor and Thomas both swung the vote to the liberals once. Roberts was never the swing justice during these years.

Next, from the 2010 Term through the 2017 Term Kennedy was the vote that swung 5-4 decisions in the liberal justices favor 25 times, Roberts was the swing justice four times (in NFIB v. Sebelius, Williams-Yulee v. Florida Bar, Artis v. District of Columbia, and Carpenter v. United States), Thomas three times, and Gorsuch once.

Gorsuch was the most frequent swing justice during the 2018 and 2019 Terms voting with the liberals in 5-4 decisions five times. This was followed by Roberts who was the liberal swing vote in three instances (June Medical v. Russo, Dept. of Commerce v. New York, and Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California).

With Barrett joining the Court in 2020 the three remaining liberal justices needed two conservative justices to swing a close vote in their favor. This happened twice with Roberts and Kavanaugh and once with Thomas and Gorsuch.

On the other end of the spectrum, Justices Alito, Scalia, Thomas, and Roberts voted together 82 times in 5-4 decisions between the 2005 and 2014 Terms. Kennedy was the swing justice for these four conservative justices in 75 of those decisions.

Judging Roberts’ success as a chief justice comes down to a matter of perspective. Since 2005, his voting behavior shows that he has mostly been a solid conservative vote in the Court’s closest decisions. Moreover, he assigned the greatest percentage of 5-4 decisions to the more conservative Justice Alito.

Even so, he did not push the pendulum in the conservative direction as strongly as Chief Justice Rehnquist. Up until the past term, he did not appear as a justice looking to balance ideological views either. His frequency of siding with fellow conservatives in close decisions only ebbed during the last term when he sided with the liberal justices almost as often as he sided with the conservative justices in 5-4 votes.

Just this week Roberts sided with the conservative justices in two cases where the liberals voted together in dissent (they were joined by Justice Gorsuch in one of the two cases).

Roberts is unlikely to be able to reel in the conservative force on the Court and so if he sides with the liberal justices on more occasions, this will not be enough to change the direction of the Court’s momentum. Looking back on Roberts’ history as a chief justice, at least from a data perspective at least, he has often been unable to achieve his most preferred outcomes.

If this is the measure of a chief justice’s control over the Court, Roberts may not have been as strong or successful of a chief as was often conveyed until the Dobbs opinion leak.

Read more at Empirical SCOTUS…

Adam Feldman runs the litigation consulting company Optimized Legal Solutions LLC. For more information write Adam at adam@feldmannet.com. Find him on Twitter: @AdamSFeldman.

[ad_2]