[ad_1]

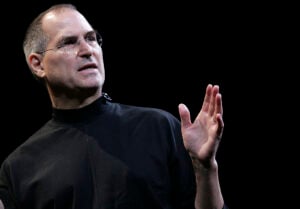

(Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Steve Jobs ushered some amazing technologies into existence. He undeniably changed American society, and the world, in profound ways.

Steve Jobs also arguably created the trope of the overconfident tech founder with a messiah complex and a “fake it till you make it” approach to ambitious business goals.

The problem for the next generation of tech founders was that Jobs actually made it. Settling into his archetype has proven disastrous for a number of more recent would-be innovators.

For years, Sam Bankman-Fried, the former CEO of now-bankrupt cryptocurrency exchange FTX, displayed a Jobs-like knack for self-promotion. Bankman-Fried cast himself as a young genius, and propelled the value (on paper) of his cryptocurrency firm to $32 billion on the strength of that image.

This was before it all collapsed.

John Ray III, the same man tapped to untangle Enron’s disastrous liquidation some two decades ago, has been put in charge of FTX in hopes of recovering at least some portion of the $8 billion in client funds that currently seem to be missing.

According to Ray, “in his 40 years of legal and restructuring experience,” he has never seen “such a complete failure of corporate controls and such a complete absence of trustworthy financial information as occurred here.”

Then there’s the cratering of fraudulent blood testing company Theranos.

Despite dropping out of college as a freshman and having no biomedical experience whatsoever when she founded Theranos at age 19, Elizabeth Holmes was hailed as a savant for the better part of her 20s, before it all came crashing down around her. It turns out the blood testing equipment Theranos was using fell far short of the science fiction-like claims the company’s founder routinely made in her many media appearances.

Holmes was known to imitate Steve Jobs, right down to the black turtleneck. She was just sentenced to 11 years in prison for fraud.

In contrast, Elon Musk seems to have secured tech success not with bluster, but with self-deprecation (at least about the odds of his several innovative business ventures). Years ago, Musk famously said of electric vehicle manufacturer Tesla, “I thought we would most likely fail.” Musk gave private spaceflight company SpaceX only a 10 percent possibility of lasting in the long run. Both of these companies are thriving.

Elon Musk obviously says strange things from time to time, and no one’s really going to accuse him of modesty, particularly not as his level of success increasingly draws sycophants into his orbit.

Still, Musk’s earlier successes seem to have been built on realistic assessments of success or failure rather than the embrace of an apparent grand destiny that has preceded the downfall of so many would-be tech entrepreneurs.

Twitter will be an interesting real world case study.

In starting Tesla, Musk said that even though the company was likely to fail, he hoped to at least disprove the stereotype that electric cars “had to be ugly and slow and boring like a golf cart.”

In acquiring Twitter, Musk took a far more grandiose tone: “Free speech is the bedrock of a functioning democracy, and Twitter is the digital town square where matters vital to the future of humanity are debated.”

Of course, it’s not apples-to-apples here compared to some new startup. Rather than getting in at the ground level like in some of his other ventures, Elon Musk acquired Twitter as a long-established company — and one that he himself acknowledged he overpaid for. Given the facts, perhaps Musk thought a little grandiosity was appropriate to the situation.

Ultimately, investors are going to decide whether confidence continues to be overvalued versus substance. There are signs, though, that the transition away from bluster as currency is already underway.

Leaders in the biotech firms looking at slowing the aging process — for dogs — have been notably circumspect in their public statements, focusing on the promise implied by real world results and the slow, methodical process of clinical trials.

Steve Jobs was one-of-a-kind. And maybe that’s a good thing.

We no longer need to be convinced of the potential posed by modern technology. Overpromising should be viewed as a red flag instead of an asset.

What we should need to see, before pouring millions or even billions into any technology company, is some actual evidence.

[ad_2]