[ad_1]

ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

on Oct 31, 2022

at 7:44 pm

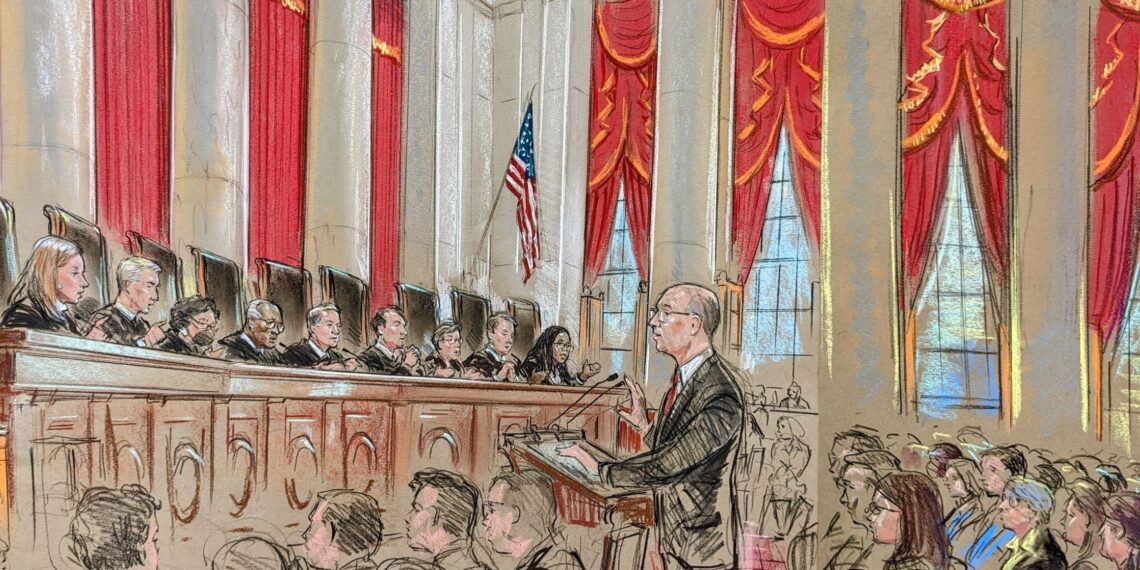

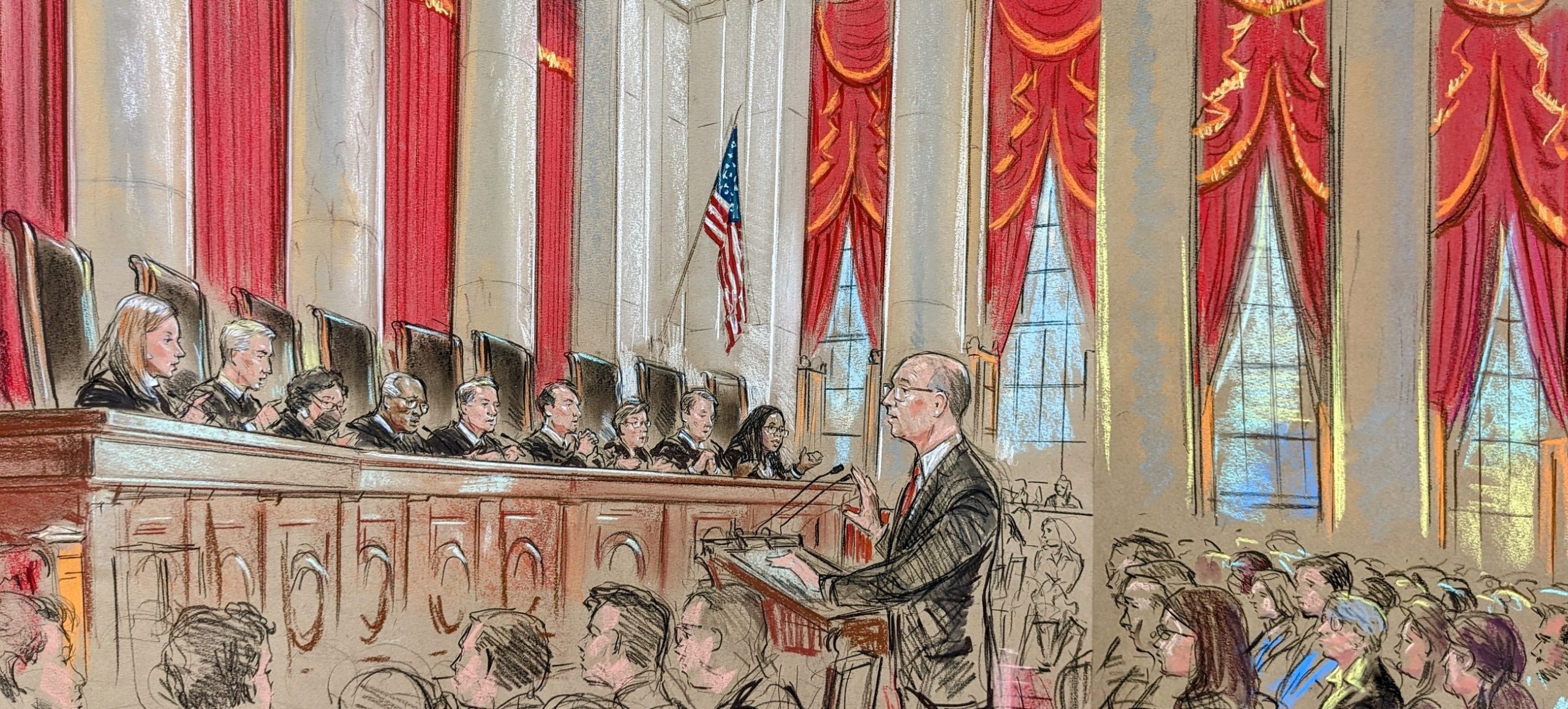

Patrick Strawbridge argues on behalf of Students for Fair Admissions. (William Hennessy)

In 2003, a divided Supreme Court ruled in Grutter v. Bollinger that the University of Michigan Law School could consider race in its admissions process as part of its efforts to assemble a diverse student body. In her opinion for the majority, now-retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor suggested that, in 25 years, “the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.” But during nearly five hours of oral arguments on Monday, the court’s conservative majority signaled that it could be ready now, 19 years after Grutter, to end the use of race in college admissions.

The lawsuits at the center of the dispute before the court on Monday were filed in 2014 against Harvard College and the University of North Carolina by a group called Students for Fair Admissions. The group maintains that Harvard violates Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which bars entities that receive federal funding from discriminating based on race, because Asian American applicants are less likely to be admitted than similarly qualified white, Black, or Hispanic applicants. The University of North Carolina, the group argues, violates the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause, which bars racial discrimination by government entities, by considering race in its admissions process when the university does not need to do so to achieve a diverse student body. Federal courts in Boston and North Carolina rejected the group’s arguments and upheld the universities’ admissions policies, prompting the Supreme Court to take up the cases.

Brown, diversity goals, and an “endpoint in sight”

Representing SFFA in the North Carolina case, lawyer Patrick Strawbridge told the justices that “racial classifications are wrong.” Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court’s 1954 landmark ruling striking down racial segregation in public schools, “finally and firmly” rejected the idea that racial classifications should be allowed to influence educational opportunities, Strawbridge said. Strawbridge urged the justices to overrule Grutter and Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, the court’s 1978 decision upholding the consideration of race in higher education.

Over the next five hours, the court’s six conservative justices leveled a barrage of criticism at the court’s precedents allowing the consideration of race, as well as the Harvard and North Carolina programs specifically. Justice Clarence Thomas, who dissented in Grutter, pressed lawyers defending the schools’ policies to explain the educational benefits of diversity. “I don’t have a clue” what diversity means, Thomas told Ryan Park, the North Carolina solicitor general representing the university.

Thomas repeated a similar question to David Hinojosa, a lawyer who represented a group of students and alumni from historically underrepresented groups who intervened in the UNC case to help defend the school’s admissions policy. What academic benefits, Thomas queried, stem from diversity?

Several justices expressed concerns about how universities determine whether they have assembled a sufficiently diverse student body and that, unless the court intervenes, universities will continue to consider race as part of their admissions process indefinitely. Justice Samuel Alito was the first to raise this issue, asking Park what the university’s goals are for diversity. How, Alito asked, can a court determine whether the benefits of diversity have been achieved?

Justice Amy Coney Barrett followed up on that point, noting that Grutter indicated that the use of racial classifications is so dangerous that it must have a logical endpoint. “When does it end?” Barrett asked. “When is your sunset? When will you know?” It has been nearly 50 years since Bakke, she noted, and that timespan suggests that achieving diversity has been difficult. “What if it continues to be difficult in another 25 years?”

U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, who argued on behalf of the Biden administration defending both schools’ policies, assured the court that “there is an endpoint in sight.” Society will change, she said, in a way that will allow universities to obtain a diverse student body without considering race.

But Chief Justice John Roberts pushed back, observing that Prelogar’s argument “was very different from what Justice O’Connor said” in Grutter. “She said race-conscious admissions programs must be limited in time. That was a requirement,” Roberts insisted.

Justice Neil Gorsuch worried aloud that Harvard’s decision in the 1920s to use a “holistic” review process was “subterfuge” for imposing racial quotas on the number of Jewish students that it admitted.

Lawyer Seth Waxman, who represented Harvard, acknowledged that Harvard was “ashamed” of anti-Semitic remarks by the Harvard president at the time. But any discrimination against Jewish applicants in the early 20th century bore “no resemblance” to the current Harvard admissions process, Waxman stressed.

Feasibility of race-neutral alternatives

The conservative justices returned throughout the two arguments to the prospect that the universities could assemble diverse student bodies using programs that do not specifically consider race – for example, providing significant financial aid or outreach programs for low-income or first-generation students. The universities and their supporters maintain, and the lower courts agreed, that although they have tried such programs, there is no “race neutral” program that will work as well right now to create a diverse student body.

Roberts pushed back, suggesting that if universities cannot consider race “then maybe there will be an incentive for the university to, in fact, truly pursue race-neutral alternatives.”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh noted that, since the Grutter decision, nine states have barred the consideration of race in the admissions process for their public universities. “Those examples now show with greater confidence,” Kavanaugh suggested, that universities can use race-neutral programs that “produce significant numbers of minority students on campus.”

Park countered that the results of those states’ race-neutral methods vary from campus to campus. “And, in particular,” he continued, “the most selective public universities are continuing to have major struggles, particularly enrolling a sufficient number of African American students, for them to reach their educational goals.”

Gorsuch noted that universities consider other factors in their admissions process, such as whether an applicant is the child of an alumnus, whether the applicant’s family has donated money to the university, or whether the applicant is an athlete. Because those preferences, Gorsuch suggested, “tend to favor the children of wealthy white parents,” should a university have to eliminate those preferences if it could then assemble a diverse student body without considering race?

Waxman pointed to the lower courts’ rulings in Harvard’s favor. Although “SFFA is fully entitled to its own legal arguments,” he told the justices, “it is not entitled to its own facts.” The facts found by the trial court, he continued, show that Harvard does not discriminate against Asian American applicants, and that it “does not yet have a current workable race-neutral alternative.”

The liberal justices push back

The court’s three liberal justices emphasized, like the lawyers defending the admissions policies, that race is only one factor among many considered by admissions officers. Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted that in the UNC case, the trial court had concluded that race, standing alone, “doesn’t account for why someone’s admitted or not admitted. There’s always a confluence of reasons. There are any number of Hispanics, Blacks, Native Americans who are not chosen by schools.”

But in the Harvard case, Waxman acknowledged that race could be a determining factor in some cases. When Waxman compared the use of race in admissions to the advantage that an oboe player might get when the university orchestra needs an oboe player, Roberts bristled. “We did not fight a civil war about oboe players,” he said sharply.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson recused herself from the Harvard case because she served until recently on Harvard’s board of overseers, but she participated actively in the UNC argument. Jackson suggested that a scenario in which universities cannot consider race as part of their admissions process, while still considering other factors like military service, might itself violate the Constitution.

She described two hypothetical applicants: one whose family has attended UNC for generations, and another whose relatives in prior generations could not attend UNC because they were Black. “The first applicant would be able to have his family background considered and valued by the institution as part of its consideration of whether or not to admit him,” Jackson said, “while the second one wouldn’t be able to because his story is in many ways bound up with his race and with the race of his ancestors.” Why, she asked, wouldn’t such differential treatment be its own violation of the equal protection clause?

And Justice Elena Kagan stressed the potential impact of a ruling in favor of SFFA on not only universities but also U.S. society more broadly. Calling universities “the pipelines to leadership in our society,” she told Strawbridge that “if universities are not racially diverse” then a broad range of other institutions – such as businesses and law firms – “are not going to be racially diverse either.”

Prelogar focused on a similar point, which had resonated with the court in Grutter. Because the U.S. military had experienced “tremendous racial tension and strife” when its officer corps did not match the diversity of its enlisted members, it is now the “consistent judgment” of U.S. “senior military leaders” that it is critical to have a diverse officer corps – which in turn requires the consideration of race for admission to the service academies, Prelogar said.

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar argues for the federal government in support of the universities. (William Hennessy)

Roberts suggested that, because of the differences between the military and universities, “it might make sense for us not to decide the service academy issue in this case.” Prelogar countered that diversity at all institutions of higher education is important to the military because of the large number of officers who come to the armed forces from university training programs.

Potential off-ramps

Gorsuch explored the prospect that the court could decide the two cases without weighing in on any constitutional issues. Although the court has held that the legal test under Title VI coincides with the test under the 14th Amendment, he noted that the language of the two provisions is different. And the text of Title VI is “plain and clear” in barring discrimination based on race.

Both Waxman and Prelogar urged the justices not to take what they characterized as the drastic step of overruling Grutter and Bakke. If the justices believe that the lower courts were not sufficiently rigorous in reviewing the Harvard policy, Waxman said, it could send the case back to them for another look. But there is no reason, Waxman added, “to dispense with decades of constitutional precedent.”

Prelogar echoed Waxman’s argument, telling the justices that to the extent that they have concerns about the slow pace of progress in achieving diversity without considering race, the proper course of action is to emphasize that the test that universities must satisfy if they want to consider race “remains very strict.” “Universities should be held to a high standard,” she continued, “and a heavy burden to explore those alternatives, to put into practice the race-neutral alternatives that currently exist, and to try to get to the point that the Grutter court imagined and that we will eventually reach as a nation where it is no longer necessary to take race into account.” But it was far from clear that a majority of justices were interested in the off-ramp that Waxman and Prelogar offered.

A decision in the cases is expected sometime next year.

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court.

[ad_2]