[ad_1]

Something is clearly different this Supreme Court term after only two weeks of oral arguments. There is a chippiness in the air that wasn’t overtly present before.

Something is clearly different this Supreme Court term after only two weeks of oral arguments. There is a chippiness in the air that wasn’t overtly present before.

The distinction between the left and the right of the Court is still in play, but newly appointed Justice Jackson has had control of the proceedings far more than her fellow justices, and there is a lot of coverage on this topic than we’ve seen before.

What does this mean for the rest of the term and for the Supreme Court moving forward? Very possibly a lot.

Control

How much does control over oral arguments matter? Some say not at all. Oral arguments, for instance, do not often clearly shift votes. The justices and their clerks have all scoured the parties’ and amici’s briefs going into oral arguments. They all have presumably read the lower court proceedings in the cases. This is enough to at least give the justices a strong feeling of how they will vote in a case before ever setting foot on the bench for oral arguments.

Still, oral arguments serve many purposes. They are important for justices to ask questions that help clarify anything not made clear in the briefs. It gives them a chance to gauge the positions of other justices. It provides them an opportunity to shoot down positions they disagree with, which is especially important if they feel other justices’ votes in the case hinge on these positions.

Even with a potential minimal effect, oral arguments have the possibility of factoring into one or more justices’ voting decisions. Even if they don’t affect votes, they may sway the justices to take a stronger or weaker view on particular issues in the case. If it is a foregone conclusion that votes are going to go down along ideological lines, then perhaps only the policy in the decision is malleable.

This is how control comes in. The ability to usurp control over arguments potentially empower justices to achieve these agenda items at the expense of others’ chances to do so. Since the start of the pandemic, Chief Justice Roberts has taken more control over arguments than any modern Chief Justice. Prior to the pandemic Roberts only started and stopped each side’s arguments. Aside from this, he asked questions like the rest of the justices. During telephonic arguments he literally divided time for the justices to all have equal questioning opportunities and played the role of moderator. Now that arguments are once again in the Supreme Court building and held in front of an audience, the Chief has still retained some of this control calling out each justice’s turn to speak. Like before the pandemic though, justices still jump in during others’ turns giving them greater opportunities to speak than existed during the pandemic.

This most recent change in the format happened just in time for Justice Jackson to join the Court. And join she did.

KBJ’s Historic First Sitting

Assuming any of the above purposes or others matter to oral arguments and how they play out in votes, opinions, or in policymaking, Justice Jackson has signaled her willingness to use this pedestal to her advantage. From her oral argument in Sackett v. EPA when Justice Jackson spoke 976 words for third most of the justices, she made her presence known. She began in a mundane way with a question of congressional intent in the agency related matter. The other justices must have found her points meaningful as they were referenced five times total in questions from Justices Kavanaugh, Sotomayor, and Barrett.

Along with her strong word count Jackson also was one of the few justices in recent memory to probe the petitioner attorney’s rebuttal with questions during the argument’s close.

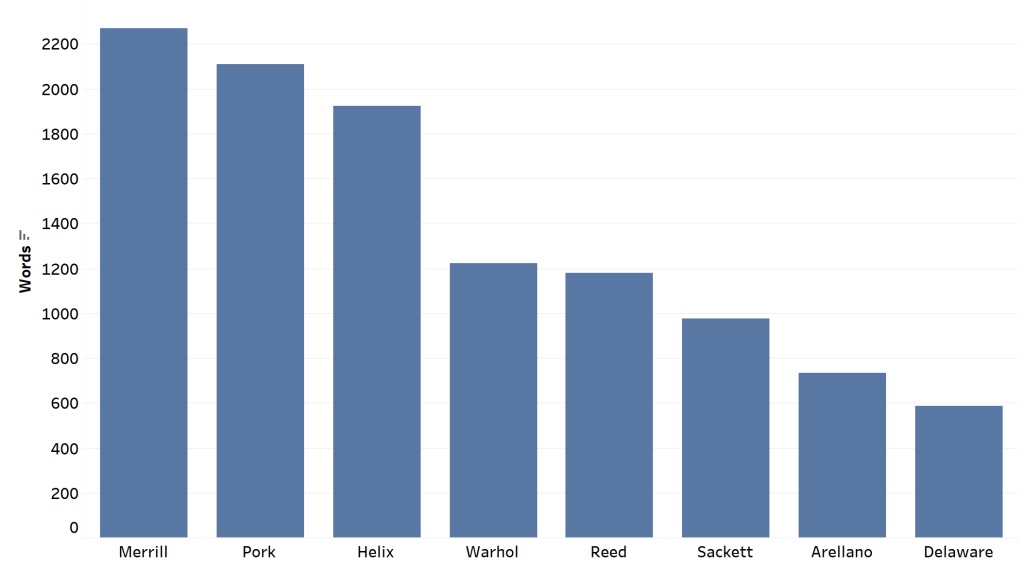

Sackett was the only argument of the eight over the first two week period of the term where Justice Jackson was not the lead speaker of the justices in terms of total words uttered. Her word count totals for all eight arguments are as follows:

Jackson’s participation in Merrill was not only notable for the 2,269 words she spoke, but also for her staking positions with claims like in response to the petitioner’s attorneys,

“I don’t think so. I think it’s to show that you have racial segregation in housing happening in this situation, that you have enough people who are in, you know, marginalized groups that another district is possible. And why is that happening? Because people are being segregated in effect, in effect, as Judge — Justice Kagan pointed out, right?”

She also has a 537 word statement/question during the petitioner attorney’s turn expositing on the drafting history of the 14th Amendment including,

“So I looked at the report that was submitted by the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which drafted the Fourteenth Amendment, and that report says that the entire point of the amendment was to secure rights of the freed former slaves.”

Not surprisingly, Jackson’s oration was criticized by the political right and praised by the left. Surprisingly, however, this was not the longest speech from a justice’s first two weeks of oral argument.

Going back at least to before Thomas joined the Court, that record is held by Justice Breyer in the case Nebraska Department of Revenue v. Loewenstein (the full audio of the argument is available at the same hyperlink) where his 593 word utterance includes among other things:

“I mean, you’ve been arguing is it really a collateralized loan, or is it really a sale? Well, it has some characteristics of each. Is a nectarine really a plum? Is it really a pear? Is it really an … I mean, it’s some of each, or whatever. All right. Suppose you start there and say, that doesn’t solve it.”

While Justice Jackson’s only non-leading word count for her first two weeks on the bench was in Sackett where she still spoke third most, this was still only just over 200 words fewer than Sotomayor who spoke the most at 1,187 words. Breyer on the other hand did not speak at all during two of his first eight oral arguments – in Hess v. Port Authority and in Allied-Bruce Terminix v. Dobson (he still authored the majority opinion in Allied-Bruce though).

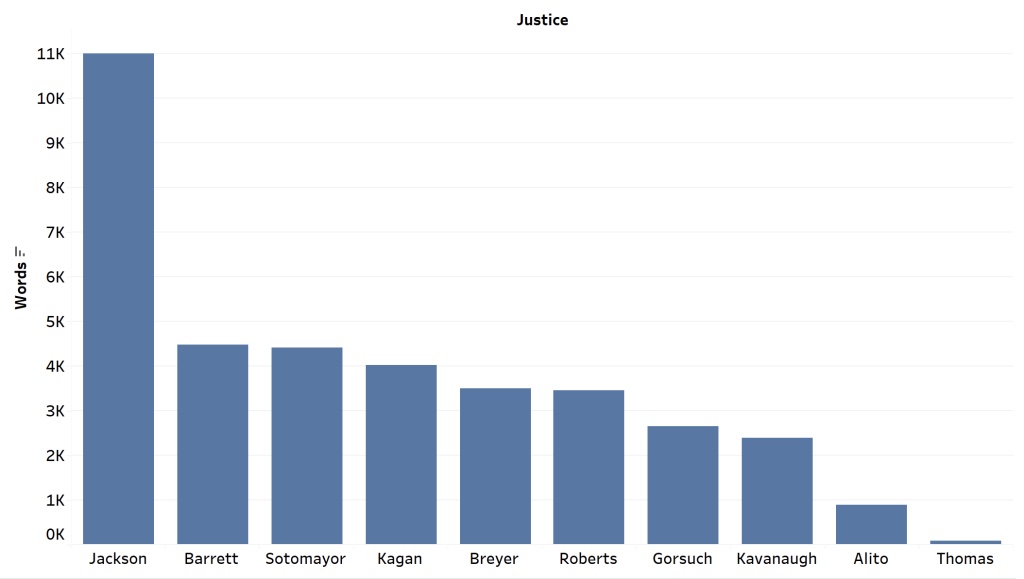

Due to Breyer’s silence during those arguments, he was not even the second most active speaker of the group of current justices along with himself. Barrett was. Breyer, however, was the only justice aside from Jackson who spoke more than 1,000 words at a single argument (1,471 in Loewenstein).

Below is a graph of the justices’ first eight argument word counts from when they joined the Court (note that Kagan’s first eight arguments were not consecutive because she recused from a number of early cases due to her involvement in the cases as Solicitor General).

Jackson’s 11,003 words is more than twice as many as Barrett who spoke 4,475 in her first two weeks of arguments.

Anecdotally, Gorsuch was described as very active in his first set of arguments as well. He was described as such due to a different unit of analysis for participation though. Gorsuch asserted himself nearly 50 times during arguments in Perry v. Merits Systems. Most of these interjections though were only a few words apiece and lacked nearly any substance.

Jackson’s activity level was noticeably different from that of her colleagues on the Court. Not only did she speak the most of the justices, but she spoke more in three separate arguments, Merrill, National Pork Producers, and Helix, than any other justice spoke that week.

She was the only justice to speak more than 2,000 words during the October oral argument sitting and she did it twice. None of the other current justices (or Breyer) spoke more than 2,000 words during their first eight oral arguments either. Breyer’s activity in Loewenstein is the highest word count in this set after the three top Jackson counts.

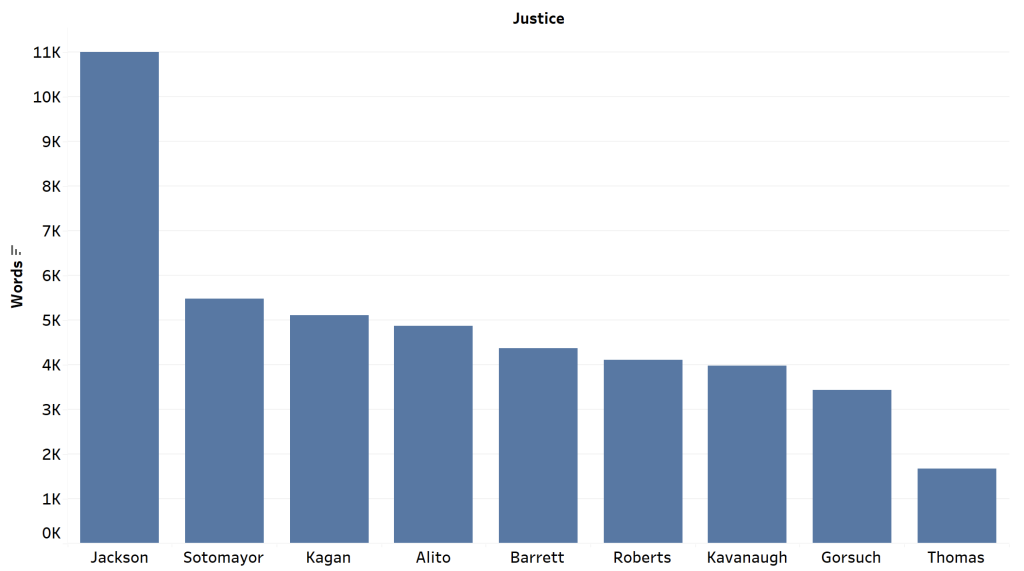

The following graph shows the justices’ overall word counts for Jackson’s first eight oral arguments.

Jackson spoke more than twice as much as Sotomayor during these two weeks and almost 6.5 times as much as Thomas during the same period.

Conclusion

The importance of oral arguments is tricky to measure as is most of their impact. We will never know for example if Jackson’s participation at oral argument persuades any of the justices to switch votes. We may not know if it affects written opinions.

Perhaps it will help the justices find cohesion in cases like National Pork Producers where, according to NBC News’ Lawrence Hurley, “the court did not appear to be divided along ideological lines, with both liberal and conservative justices offering a variety of bleak hypothetical questions about how a ruling in favor of either side could affect the delicate relationship between states.”

Outside of the justices’ votes, though, the coverage of her participation and the remarks she makes in cases like Merrill have the prospect of changing the narrative of cases and the way the public consumes them. This, however, may only widen the public’s (and the Court’s) ideological divide moving forward.

Read more at Empirical SCOTUS…

Adam Feldman runs the litigation consulting company Optimized Legal Solutions LLC. For more information write Adam at adam@feldmannet.com. Find him on Twitter: @AdamSFeldman.

[ad_2]