[ad_1]

Many years ago, I worked as a law enforcement officer in the ranching country of western South Dakota. Every August, my community hosted a five-day stock show and rodeo. Friday night of the stock show was always highlighted by a big-name country music star. I had the privilege of providing security for country music stars such as Mel Tillis, George Strait and Louise Mandrell. I offered to take Tillis bass fishing the day after his appearance. He wanted to take me up on my offer, but he didn’t have the time.

In addition to attracting big-name country music stars, the annual stock show drew some of the best rodeo riders from across the upper Great Plains. One popular rodeo event was calf roping. When a cowboy on horseback signaled they were ready, a chute opened and a calf ran out toward the center of the arena. As the calf left the chute, a lever was tripped, starting a timer. A cowboy on horseback would race up to the calf, lasso it, then dismount and take the calf to the ground. Grabbing a short length of rope, the cowboy attempted to tie three of the calf’s legs together as the clock continued to tick away the seconds. When the legs were tied, the cowboy threw his arms into the air, stopping the clock. The winner of the calf-roping event was the cowboy with the quickest time. The winning time for a calf-roping event was typically under 10 seconds.

Having the quickest time is all well and good if you’re a cowboy attempting to win a calf-roping contest. If you’re a law enforcement officer, however, rushing to end calls too quickly can often have disastrous results. Each call an officer responds to has its own unique set of circumstances and should not be approached with a one-size-fits-all perspective.

Avoiding the need for force and seeking voluntary compliance from a subject should be an officer’s objective whenever possible.

In recent years, the importance of officers de-escalating situations has garnered much national attention. The word “de-escalation” is everywhere these days. Whether you call it de-escalation, non-escalation or force avoidance, the bottom line is that officers should do what they can, when they can, to not escalate a situation. Avoiding the need for force and seeking voluntary compliance from a subject should be an officer’s objective whenever possible. Officers who view time as an ally have a much greater chance of achieving that objective.

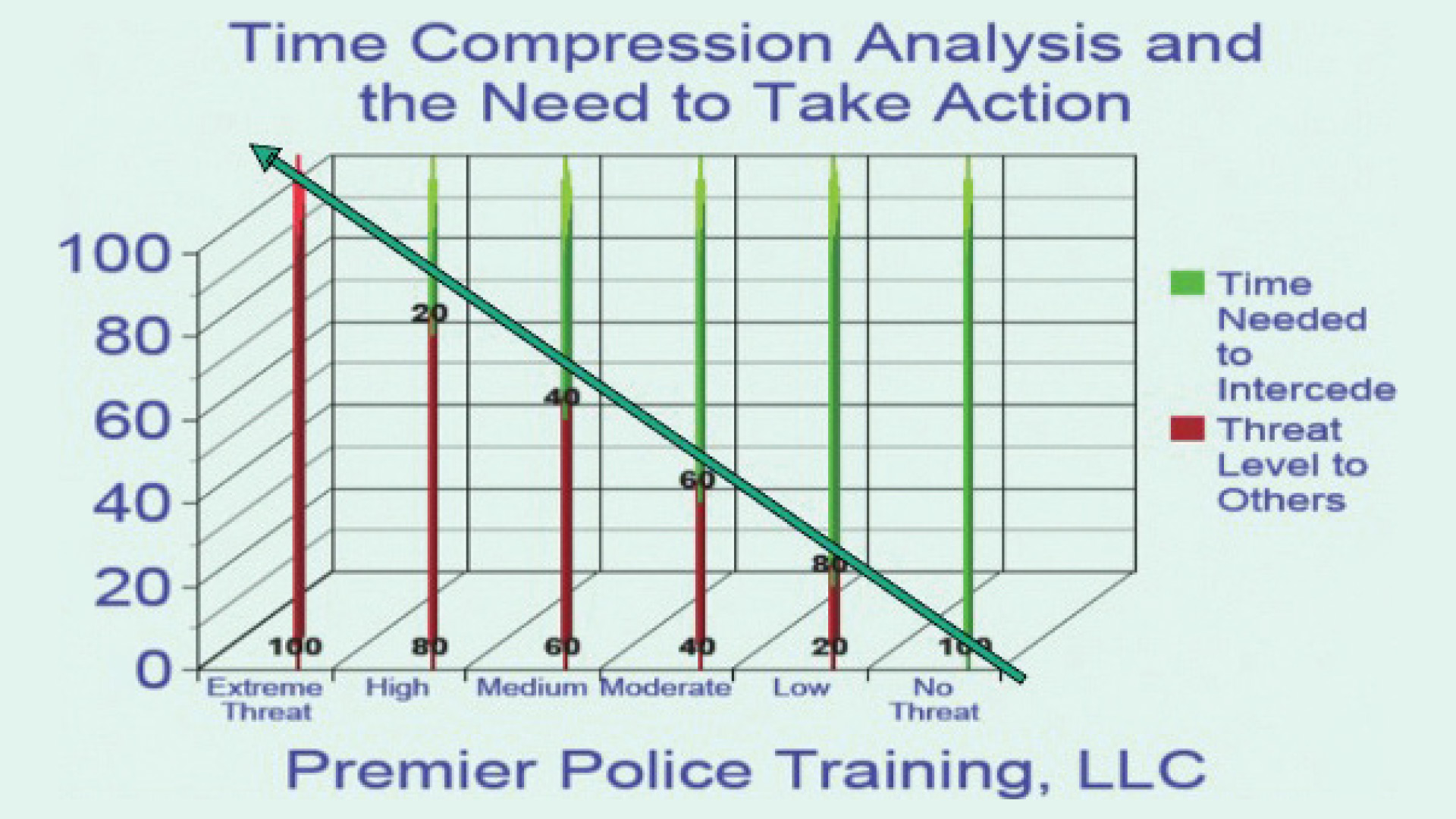

Research and experience have clearly demonstrated to me that unnecessary compression of time is a leading contributor to a phenomenon I call officer-induced escalation. Research and experience have further demonstrated a directly proportional relationship between unnecessary time compression and the eventual application of unreasonable force. When officers compress time unnecessarily in their rush to end an encounter or enforce a command, the chance of applying force increases significantly, often unreasonably.

A recent example of unnecessary compression of time occurred when an officer performed a traffic stop for a minor traffic violation. The officer approached the car and said, “Officer Stone with the city police. License, registration and insurance.”

The driver responded, “May I ask why you pulled me over?” Immediately, the officer replied, “After I get all your documents, I will tell you that.” The driver still didn’t know why he had been stopped, so he asked, “Isn’t it OK if I ask that question?” The officer reached down and opened the driver’s door, saying, “OK, step out of the vehicle, now!” The officer then took hold of the driver’s arm and attempted to pull him from the car. The amount of time from first contact with the driver to going hands-on was approximately 16 seconds.

How we treat people and how we talk to them do matter. Officers who have been trained in procedural justice understand this concept well. For police officers, procedural justice includes four basic actions:

- Treat people with respect.

- Listen to what they have to say.

- Make fair decisions.

- Explain your actions.

Procedural justice also stresses the importance of giving people a voice by taking the time to answer citizens’ questions and explaining our actions to them. Preliminary research has demonstrated that police officers who slow down their encounters with the public and practice more respectful and empathetic communication can reduce the need for force and garner higher levels of voluntary compliance.

Obviously, there are calls for service when time is of the essence. Active killers, domestic situations involving violence and accidents with serious injuries are three examples of calls that mandate a quick response and quick action once an officer arrives on scene. These situations require an officer to necessarily compress time, as lives may be in peril.

Conversely, there are calls for service where a quick response may be required, but quick action after arrival is not. In these situations, time is often on your side. A particular example of this involves people who are experiencing emotional or mental crises and pose a threat only to themselves.

A little over a year ago, officers were called to a report of a suicidal man who was standing outside of his home holding a small container of fuel in one hand and matches in the other. At this point in time, the subject posed a threat only to himself. Upon arrival, all three officers rushed in and began screaming orders for the man to drop the items and get on the ground. In the chaos, one officer deployed his Taser, and another officer discharged his firearm at the subject, killing him. The entire event, from the moment officers arrived on scene to the moment the subject was killed, was less than 30 seconds. The combination of proper communication skills and using time to your advantage is critical in instances such as this.

There are other factors that affect the length of time officers spend on a call for service. Many agencies are experiencing personnel shortages that directly impact patrol officers. When calls for service become unreasonably stacked due to undermanned shifts, patrol officers can feel undue pressure to clear calls quickly so they can get to the next call. Responding officers shouldn’t be expected to compromise their safety, the safety of the public or the time they need to properly respond to and investigate calls for service.

I understand the complexities facing agency administrators in eliminating or minimizing these challenges. Paying officers overtime to work open shifts can provide some temporary relief, but an additional problem may surface in the form of officer burnout. Some agencies are covering shifts with administrative officers, up to and including chiefs and sheriffs, while others are expanding their hiring of part-time officers, particularly retired officers. Retraining dispatchers to better prioritize calls for service is also being undertaken by a growing number of departments. If a call for service is not law enforcement–oriented or doesn’t require a law enforcement response, the call should be assigned to the appropriate non-enforcement entity and not be pushed out to patrol officers.

Time is one of the most important and effective tools you have available to you as an officer to avoid force and obtain voluntary compliance. Whenever possible, use time to your advantage. Slowing things down by not unnecessarily compressing time is a simple yet highly effective tactic available to officers to avoid force and obtain voluntary compliance.

Remember, law enforcement is not a rodeo. In most police–citizen contacts, the clock is not ticking. Use time as an ally, and slow down so you can think.

[ad_2]